Reduction and Inscription: Inscribing on the Erased Terrain

Yueling Li - July 2, 2023

Figure 1: “Clouds and Rain,” Florentine Codex, vol.2, fol.238r. Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana/Donato Pineider, Florence, Italy.

The materiality of a medium, the peculiar techniques required to produce it, and the labor process all are subtle manifestations of meaning, symbols and allegory. These dimensions are so evident that they are often silenced when conducting visual analysis, yet they do constitute and complete the physicality of inscription. Prints often evade the discussion of materiality because of their replicative nature, which allows mass-production and fluidity in the vessel paper medium. I will study the relationship between European printing tradition and its derivational artworks in New Spain. I propose that the European printmaking tradition prescribes a violent and reductionist pictorial pattern that aims to hurt the land and to eradicate unclear boundaries. As this gets mobilized to the New Spain, however, the locals modify the print media with various additive methods that inscribe indigenous symbols and representations onto the template. As much as the print media erases, it shares the same peril of slippage and an anxiety of uncontrollability, just as all forms of authority do. In response to the reductionist European technology, the “less advanced” population of “savages” modified the rules, symbols and imagery in prints onto their native surface and pictorial territory. In many cases, these are additive methods in contrast to the subtractive woodcut, etching and engraving. Be it the gathering of feathers, the layering of pigments and ink onto ámate paper or the hand drawn map grids, these objects add presence and historical, cultural and religious context onto the European traditional template.

The process of engraving is both violent and reductionist. On one hand, it engraves by doing damage to the plate. Opposite to the woodcut technique, the ink is retained in the engraved incisions instead of the plate. Inscription is achieved by producing scars. Message and meaning are carried within the ridges of carving, within the irreversible damage done to the plate. Ink, like blood, flows through the hollow veins and then bleeds onto the transferred paper surfaces. The technique therefore can be seen as a formal manifestation of the bloodshed done on the pictorial terrain. On the other hand, the procedure of engraving, like all print techniques, is reductionistic. It requires cutting out lines, eliminating a portion of the physical space and arbitrarily preserving the other scarred territory. It erases, compresses and flattens the space to make the ruins stand out. Combining these two aspects together, this particular procedure of making an engraving print can be seen as a miniature realization of the European colonization ideology. Such is cartography, when the arbitrary grid, establishment of churches and cross symbols flatten the cartographic space and erase glyphic marks and other indicators of historical and humanistic presence of the indigenous population. Patricia Seeds proposes that each European colonization culture practices an arbitrary ceremony of possession.1 I would argue that the printing medium is also such a ceremonial pictorial strategy, as its production reflects a reductionist principle and an arbitrary top-down elimination of space. The mobility of prints further weakens the physical importance of base—it is a pattern, a template that can be inked on almost all kinds of surfaces. It is a set of rules manifested in lines and ridges that can be imposed upon virtually any surface. The circulation of prints is therefore more than an introduction or exchange of art and craft; it is a visual colonization process that invades and announces its presence upon the other.

How do the native inhabitants of the invaded territory respond to this visual colonial ceremony? They take the skeleton template of the engraving and add organic, moving, and lively layers. The illustration Clouds and Rain in the Florentine Codex (Fig. 1) adds one dimension to the incision plate: wash. On a purely visual dimension, residues of a liquid medium precipitate on the paper, mingling with the ink lines that mimic the engraved ridges. It rains on the drought, barren scarred land, filling the scars with flowing wash. It introduces mobility and fluctuations to the precise defined boundaries. Besides the visual confusion and blur created by the wash, it also provides a shelter and safe space for Nahua religious glyph to exist. The Florentine Codex is intended to present the Nahua history and culture to the European audience and justify for the native population’s intellectual capacity as well as their non-savage, non-idolatrous spiritual practices. Therefore, direct portrayal of any deity or idols is absent in the codex. As Todd Olson comments in his essay, “The forbidden god was enmeshed in a dense graphic system that had developed independently of alphabetic inscription”.2 Symbolically, the curly glyph adds an indigenous visual culture to European naturalism, while utilizing the technique of cross-hatching to innovate a new non-volume suggestion of space. Fractal-like swirls of clouds intertwine, repeating patterns and reiterating the motif; yet each curvature, drawn by Nahua tlacuilos hand, retains a unique distinct shape. No two strokes are identical; they deviate and develop from a standard form, defying exact replication and standardization. Unlike a print which assures each outcome would be molded to an exact, predetermined shape, the drawing undermines this control of the pictorial space, and challenges the top-down authority imposed by the colonizer culture. Therefore, as the drawing pays homage to the European engraving through imitating cross hatching, it also simultaneously claims autonomy.

Following the discourse of cross hatching in the previous example, we shall further explore the technique on a larger scale. Cross hatching (Fig. 2) forms minuscule grids, trapping pixels of space between lines. To zoom out, cross hatching resembles the justification behind the grid logic in European cartographic traditions. It deconstructs a blank void into smaller restrictive cells, endowing a greater sense of control over the territory. This is exactly what the Church missionaries did—arbitrarily setting squalid districts, imposing a network of grids to capture and contain the conquered New Spain. Spinning off from Dana Leibsohn’s work, we can construct a parallel between the mapping grids and the cross hatching marks.3

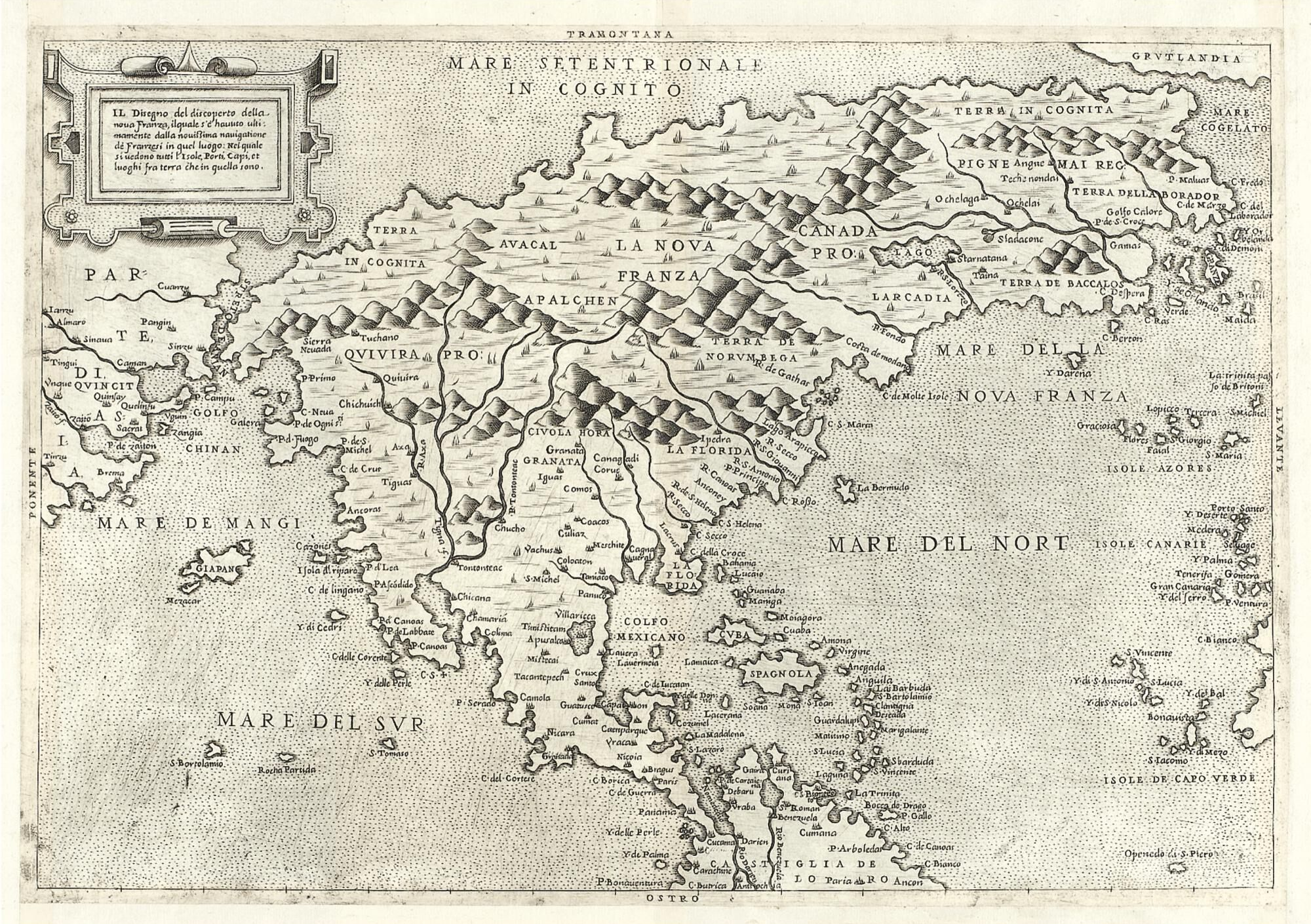

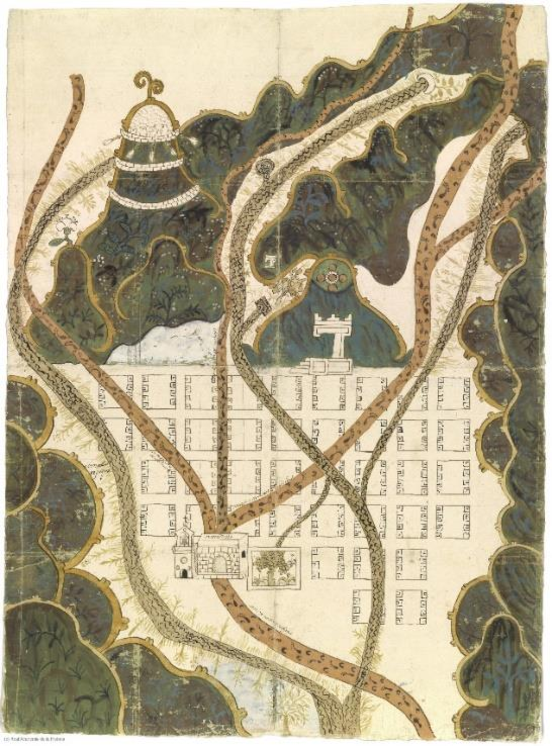

The European map, exemplified by the engraving Il Disegno del Discoperto della Nora Franza (Fig.3), features clearly defined boundaries between regions. Landscapes such as mountains, rivers and coasts are conventionalized in a uniform flattening representation. The shaded triangles mark hills, the inking contours stand in for rivers and water bodies, and regions are distinguished by their nominal labels. These formal repetitions are reassured by the print medium, guaranteeing consistency and uniformity. Once again, when such tradition is absorbed and adapted by the indigenous map makers and tlacuilos, the certainty is disrupted by the hand-drawn markings. In the Texupa map (Fig. 4), one can observe thick stripes pierce through the pre-established grids and hover over the space, guarding the terrain and overriding the Spanish invaders’ rules. The shadowy hills surrounding the divided city seem to all be connected and merging toward the center. They encompass the grid, threatening to devour the European-dictated boundaries in an immense dark void. The grids on the Texupa map therefore become a matrix for local particularity, allowing a palimpsest of layering that may undermine definition, clarity and boundary.

As we advance into higher dimensionality and voluminosity of the additive media, the medium does not restrain itself to be bound by paper, and often takes on a three-dimensional form. The feather mosaic of Mass of Saint Gregory (Fig. 5) is the ultimate antithesis to reductionism—it is all about the addition, collective construction and physicality of materials. Pixels, or rather voluminously, voxels of organicity gather and agglutinate on the board, weaving a map of symbols, glyphs and double sided meanings. Every fiber of the feather is minced, deconstructed, and annihilated from its original integrity, nothing like what is attached on a bird. Yet when each of the pulverized individuals are collected together, they realign into a design that evokes indigenous tradition in addition to the Christian visual formula (Fig. 6). Indigenous craft and devotional practice surrounding the use of feather, which is a mobile, trade object of exchange among a larger pre-Hispanic American communities. As a gift to the pope expressing gratitude for the grant of indigenous autonomy, it demonstrates the power of claim for human status and non-slave, de-objectification. The mosaic does not merely replicate the catholic model of symbolic embodiment, but through depicting the same scene via the additive medium of feather work, it also addresses the power and justification of the Nahua glyphic tradition and belief system. The Catholic signs and testimonial relics of the miracle are endowed with a second valence of meaning in the feather work. They bear a double-sided inscription that documents and preserves indigenous glyphs, metonymy and spiritual embodiment.

In each of these instances, we see the European skeleton is covered, devoured and digested by the indigenous accommodations, and has manifested in a new flesh and vein that flows the blood of the oppressed, the violated, the silenced people. European prints and their New Spanish counterparts are prime examples of anthropofagia, as native habitants in the colonial New Spain utilizes a variety of media to respond to the imported engraving convention. The works they produce collectively aggregate into a self conscious world to perpetuate indigenous culture and identity, especially amidst the suppression and invasion of colonization.

Notes

1 Patricia Seed, Ceremonies of Possession in Europe's conquest of the New World, 1492-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

2 Todd Olson, “Clouds and Rain,” Representations 104, no. 1 (2008): 102.

3 Dana Leibsohn, “Colony and Cartography:Shifting Signs on Indigenous Maps of New Spain,” in Reframing the Renaissance:Visual Culture in Europe and Latin America, 1450-1650, ed. Claire Farago (New Haven: Yale University Press): 279.

Bibliography

Leibsohn, Dana. “Colony and Cartography: Shifting Signs on Indigenous Maps of New Spain.” In Reframing the Renaissance: Visual Culture in Europe and Latin America, 1450-1650, edited by Claire Farago, 265-81. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Olson, Todd. “Clouds and Rain.” Representations 104, no. 1 (2008): 102–15. https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2008.104.1.102.

Seed, Patricia. 1995. Ceremonies of Possession in Europe's Conquest of the New World, 1492-1640. ACLS Humanities E-Book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.01808.