Preferring Multiple Choice: The Serial Figure of Batman Translated Across Mediums

Katherine Terrell - May 15, 2023

“Na na na na na na na na na na na na na… Batman!”

Batman is everywhere. On lunch kits, shirts, and backpacks, the icon of Batman is plastered on a plethora of peculiar objects and depicted in a multitude of different versions. He is a figment of popular culture, much like his pal (and occasional rival) Superman. He is one of the most well-known serial figures, which are figures “that recur with the same …repeatedly mutating- properties.”1 Those familiar with the masked man dressed as a bat (not to be confused with the villain Man-Bat) almost certainly have their favorite portrayal of the Caped Crusader. Many diehard fans will often argue over their favorite Batman actors as well as their favorite writers or artists.

As a serial figure, the narrative of Batman is ever-changing and evolving. Even if a specific series or movie has ended, the canon of Batman carries on thanks to continuous consumer consumption. The more the public demands Batman, the more iterations of the character are produced, and the more the serial figure evolves. As Frank Kelleter explains in Five Ways of Looking at Popular Seriality, “...the more their proliferation tells its own story…the more these serial figures allow…increasingly rounded incarnations that can explore alternative shapes and nuances in great detail.”2 Batman began in 1939 as a fun, campy comic, with the Caped Crusader consistently winning and capturing the crooks.3 With a circular story arc, frequent consumers of the comic knew that each issue would be similar to the last one: the villains are captured and thrown in jail, just to escape eventually, for Batman to capture them again, and on and on.... But over time, that narrative evolved slowly. No longer would this serial deferral continue. Instead, as the comics developed, the plot became more variable and writers were given more creative freedom with the character. Now Batman stories could last a single issue, a single movie, or a single book, and authors could kill off characters or even age the seemingly perpetually youthful Batman.

No longer was Batman campy, no longer could Batman save every person, and no longer was Batman perfect and ideal. Not only were the stories more realistic, but also darker and less comedic, leaving viewers with stories such as Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986), Batman: The Killing Joke (1988), and Batman: Year 100 (2006). But in recent years, the medium of Batman—from films, comics, TV, characters, and even to the city of Gotham itself—has gradually regained some of its goofiness, with films such as The LEGO Batman Movie (2017). As Shane Denson and Ruth Mayer claim, “...serial figures reflect and document the evolution of media forms in a marked and condensed manner.”4

Comics have traditionally been considered (and stereotyped as) a childish medium in the past because they were primarily marketed towards children and teenagers (although in the Golden Age many soldiers read comics), and were often associated with genres such as superhero stories or funny cartoons. Additionally, the simple, colorful art style and use of speech bubbles to convey dialogue made them appear less sophisticated than other forms of literature. Films have typically been considered a more profound medium of artistic creation. The two artistic media discussed here shatter those assumptions. The comic Batman: The Killing Joke is not in the least bit childish, instead involving a darker color pallet and more serious thematic elements. In contrast, The LEGO Batman Movie is not serious (as one would expect from recent Batman films); instead, it is silly and lighthearted. Although Batman: The Killing Joke and The LEGO Batman Movie are different mediums, with contrasting levels of seriousness, they offer an intriguing look at the overall medium of Batman when examined together.

Batman: The Killing Joke:

Batman: The Killing Joke is one of the most iconic and controversial Batman stories of all time. Written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Brian Bolland, the comic was first published in 1988 and has since become a staple of the Batman canon. (John Higgins was the original colorist, but here I’ll be referring to the recent re-color by the original artist Brian Bolland for the Deluxe Edition release of the comic.) The story centers around the relationship between Batman and the Joker and explores the Joker’s origins. The Killing Joke is a story that not only comments on the Batman narrative structure but also on the medium of comics as a whole.

The comic features two parallel stories: one in the present and one in flashbacks that establish the origin story of the Joker, which would eventually become canon. In the present, Batman examines his relationship with the Joker, his main nemesis. The Joker is integral to Batman's story, but their never-ending cycle of conflict raises the question of how much longer their relationship can be deferred. The comic's ending (partially) answers this question.

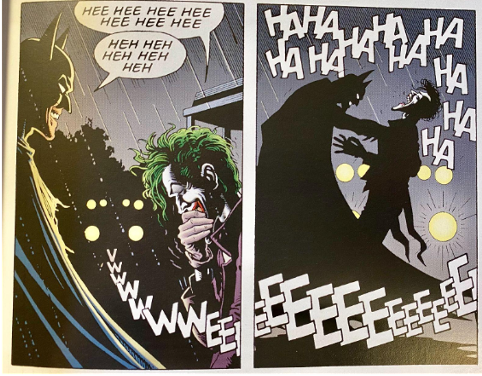

Figure 1: Panel from Batman: The Killing Joke, Deluxe Edition written by Alan Moore, illustrated and re-colored by artist Brian Bolland (1988 original release, 2008 re-colored release)

While presenting a complex narrative, this dark story also says much about the medium of comics and how it is utilized to tell said story. Batman: The Killing Joke is narrated by the ultimate unreliable narrator: The Joker. He even admits to his own uncertainty, as he has disparate memories of a single event, saying that “Sometimes I remember it one way, sometimes another...If I’m going to have a past, I prefer it to be multiple choice!” (Figure 1). The concept of "multiple choice" is central to the idea of Batman and the serial figure, as there are multiple stories, authors, and actors. The individual story, as a single narrative, is incomplete and essentially “unreliable,” for it disregards the rest of the Batman canon.

This Batman story is unique in its narrative structure, residing in a middle ground between a continuous narrative and a self-contained single story. At the very end, the Joker says that the situation reminds him of a joke about two inmates in an asylum who try to escape. Batman chuckles at the joke’s punchline, and the two old foes share a laugh (Figure 2). This ending is left ambiguous, leading to different interpretations and sparking debates among fans. Some see the ending as a resolution to Batman and Joker's long-lasting feud. Another alternative interpretation, popularized by comic writer Grant Morrison, is that Batman kills the Joker at the end of the story, hence the title “The Killing Joke.”5 This ambiguity allows the story to potentially be both a continuous narrative and offer narrative closure. So this story is stuck in a purgatorial middle ground, offering the ultimate possibility of being both. As a result, the story can continue to evolve, promising perpetual renewal, which is essential for a superhero narrative.

Figure 2: Panel from Batman: The Killing Joke, Deluxe Edition written by Alan Moore, illustrated and re-colored by artist Brian Bolland (1988 original release, 2008 re-colored release)

Batman: The Killing Joke is also aware of the tactile comic medium and its circular repetition, as shown by the identical first and last panels depicting rain hitting the ground. This stylistic choice is once again a reminder of the very medium of Batman and that of serial deferral (how the end is defered to the next issue, and the next one, and so on); regardless of how this story ends, some version of Batman will always lock up the bad guys, they’ll escape, and the narrative will repeat itself repeatedly. The physical material of the book is a singular narrative, but also one story that has been built on the backs of past material and will influence future narratives. This comic was not directly created as part of the canon, but the new origin of the Joker became canon regardless of intentions. This comic narrative evaluates and questions both the basic structure of a Batman comic and what counts as comic canon. Finally, the comic references previous Batman histories through direct references to characters such as Two-Face, Catwoman, and the Penguin, and an image of the Bat-family on Batman's desk, linking this narrative to previous iterations of the character. Batman: The Killing Joke is aware of traditional comic mediums and plots and uses that awareness to its advantage.

The LEGO Batman Movie (2017):

Many people tend to write off The LEGO Batman Movie as not an actual Batman film, but arguably it is the most Batman of all the Batman films. This Batman film references the entire existence of Batman.

The film’s beginning narrative reflects on the Batman medium and entirely subverts it. As soon as the film begins, the common citizens aren’t afraid of the Joker. To this, the Joker is perplexed, as is the audience to some extent, and says to his victims, “You should be terrified.” To which the two captive citizens respond, “Batman will stop you. He always stops you.” This retort reflects the larger story of Batman and the Joker. Batman always catches the Joker; it is simply part of the medium of Batman.

Figure 3: Screenshot from The LEGO Batman Movie (2017)

The LEGO Batman Movie also references the Batman narratives that came before it by bringing in 39 different Batman villains from Batman’s past.6 The villains of this film span multiple decades and various mediums including the comics, television shows, and movies. This crazy number of villains is the most Batman foes that have yet to appear in one singular Batman film. It is also worth mentioning that the Red Hood makes a small appearance in the movie; he was initially the alter ego of the Joker and is in the Joker’s origin story from The Killing Joke!

Along with all the villains across mediums, this film also has other references to alternate Batman mediums that came before this film. Batman’s song at the beginning of the film lays out what Batman is best known for in other movies. The “Na, Na, Na, Na, Na, Na, Na, Na, Batman!” part of the song pays homage to the 1960s tv show theme song, with another nod to the tv show theme song coming later in the film in the form of the Bat-Mobile horn! Furthermore, this Batman film directly acknowledges that the Batman medium is very old. During Barbara Gordon's speech, she says that “Batman’s been on the job for a very, very, very, very, very, very, very, very long time,” and after that remark, Bruce Wayne says that “He has aged phenomenally.” This Batman film references the entire medium of Batman through traditional (and circular) plot structures, villains and homages to earlier decades and mediums, and finally, through the tremendous old age of Batman.

The LEGO Batman Movie also interacts with the concept of other non-film mediums. There is a remarkable reference to the medium of comics. In the last fight scene, there are cheesy sound effects bubbles, and Batman then explains what sound effects are to Robin and the viewer. “Okay, Robin. Together, we’re gonna punch these guys so hard, words describing the impact are gonna spontaneously materialize out of thin air” (Figure 4). The LEGO Batman Movie is not trying to recreate the comic book version of Batman on screen; instead, it’s trying to create something new to add to the long history of Batman.

Figure 4: Screenshot from The LEGO Batman Movie (2017)

Conclusion:

The Killing Joke and The LEGO Batman Movie offer drastically different depictions of the character of Batman, although there are similarities in the characteristics of the character. There have to be similarities, or fans would not recognize and accept both versions as the character of Batman. But the two Batmans are also different. The Batman from Batman: The Killing Joke seldom smiles and doesn’t banter back and forth; he is mostly a quiet, thoughtful figure. In contrast, Batman in The LEGO Batman Movie bursts into song not even 10 minutes into the film. According to Denson and Mayer, “Successful serial figures are marked by their openness and indeterminacy; they lend themselves to transhistorical adaptation and appropriation.”7 So for Batman to be an excellent serial figure, he needs to be adaptable across a time gap and able to radically evolve. (What’s more radical than a LEGO figurine?)

It is also important for there to be narrative similarities as well, and both narratives question the relationship between Batman and the Joker. At the beginning of the Batman: The Killing Joke comic, Batman reflects on his and the Joker’s relationship. He sits down to play a game of cards with the Joker and says, “I’ve been thinking lately. About you and me.” This contemplation is similar to The LEGO Batman Movie, in which the Joker thinks he and Batman have some kind of “greatest enemies” relationship. The conflict surrounding both figures leads to a similar ending in both iterations of the story. In Batman: The Killing Joke, the two laugh together like old friends (regardless of the non definitive end of the narrative). The LEGO Batman Movie features a scene with romantic comedy undertones in which Batman and the Joker finally come to terms with their relationship. As the sun sets and the two stand close to each other, Batman says, “I’m just gonna come right out and say it. I hate you, Joker.” Joker responds, “I hate you, too.” In the end, both of these stories are about Batman and Joker’s relationship and how this relationship is central to the overall Batman medium.

The Killing Joke and The LEGO Batman Movie together explain how different mediums from different decades explore the overarching medium of Batman. Both works explore ideas of narrative closure and serial deferral while building on past Batman narratives and influencing future ones. These medias use devices like unreliable narrators, ambiguous endings, and circular endings to question the medium and the serial figure of Batman. This serial figure has changed, while maintaining some core characteristics, across time and across translations between comic to film. These Batmans are just two versions in the long history of the story. In the words of the Joker, “If I’m going to have a past, I prefer it to be multiple choice!” Batman, as a serial figure, embodies this idea of multiple choice; there isn’t just one version of Batman. But, through it all, adaptation is essential to the continuation of Batman for future generations, and in the words of Will Brooker, “...it is through being adapted that Batman has survived.”8

Notes:

1 Kelleter, Frank. “Five Ways of Looking at Popular Seriality.” Media of Serial Narrative, 2017, 8. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv10crd8x.5.

2 Kelleter, “Five Ways of Looking at Popular Seriality”, 22.

3 The character of Batman debuted in May 1939 in Detective Comics #27. He didn’t get his own comic book run until 1940.

4 Denson, Shane, and Ruth Mayer. “Border Crossings: Serial Figures and the Evolution of Media.” NECSUS: European Journal of Media Studies 7, no. 2 (2018): 66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3460.

5 McMillan, Graeme. “Did the Dark Knight Secretly Kill His Archenemy 20 Years Ago?” The Hollywood Reporter. The Hollywood Reporter, August 17, 2013. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-features/did-dark-knight-secretly-kill-608209/.

6 The less well-known villains include Calendar Man, Bane, Captain Boomerang, Catman, Clayface, Mr. Freeze, Clock King, Zebra-Man, Zodiac Master, Condiment King, Crazy Quilt, Eraser, Egghead, Gentleman Ghost, Killer Croc, Killer Moth, King Tut, Kite Man, March Harriet, Mime, Mutant Leader, Orca, Polka Dot Man, Scarecrow, Tarantula, Calculator, Dr.Hugo Strange, Doctor Phosphorous, Kabuki Twins, Magpie, and Red Hood. The popular villains include Two-Face, Riddler, The Penguin, Catwoman, Harley Quinn, Poison Ivy, and of course Joker. There’s also the freaky Man-Bat!

7 Denson and Mayer, “Border crossings: Serial figures and the evolution of media,” 74

8 Brooker, Will. “Batman: One Life, Many Faces.” Essay. In Adaptations: From Text to Screen, Screen to Text, edited by Deborah Cartmell and Imelda Whelehan, 197. London: Taylor and Francis, 2013.

Bibliography:

Brooker, Will. “Batman: One Life, Many Faces.” Essay. In Adaptations: From Text to Screen, Screen to Text, edited by Deborah Cartmell and Imelda Whelehan, 185–98. London: Taylor and Francis, 2013.

Denson, Shane, and Ruth Mayer. “Border Crossings: Serial Figures and the Evolution of Media.” NECSUS: European Journal of Media Studies 7, no. 2 (2018): 65–84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/3460.

Kelleter, Frank. “Five Ways of Looking at Popular Seriality.” Media of Serial Narrative, 2017, 7–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv10crd8x.5.

McMillan, Graeme. “Did the Dark Knight Secretly Kill His Archenemy 20 Years Ago?” The Hollywood Reporter. The Hollywood Reporter, August 17, 2013. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-features/did-dark-knight-secretly-kill-608209/.