Go On Out, Get Some More: Edward Colver and the Photographic Legacy of Hardcore Punk, from “Damaged” to “Die Lit”

Zeki Hirsch — November 13, 2021

All photographs by Edward Colver.

Photography has always been an integral part of music. As a visual medium working hand-in-hand with a sonic medium, photography has given not only faces to names, but also images to sounds. With the British Invasion of the early 1960s, widely circulated photographs of The Beatles’ stadium-filling, eardrum-bursting early shows gave fuel to the rising flame of Beatlemania. After Woodstock, Henry Diltz’s vivid pictures of Jimi Hendrix’s set created the perfect companion to Hendrix’s iconic rendition of The Star-Spangled Banner that became a countercultural anthem. In 1976, as radio stations were inundated with sluggish progressive rock and bland glam pop, the global soundscape of music changed forever with the first true punk rock movement that exploded in downtown New York City. Acts like the Ramones, Patti Smith, the Dead Boys, and the Heartbreakers embraced a newfound DIY attitude that was perfectly encapsulated by the work of photographers Bob Gruen and Ebet Roberts. Just like the bands themselves, the names of these photographers became synonymous with the word “punk.”

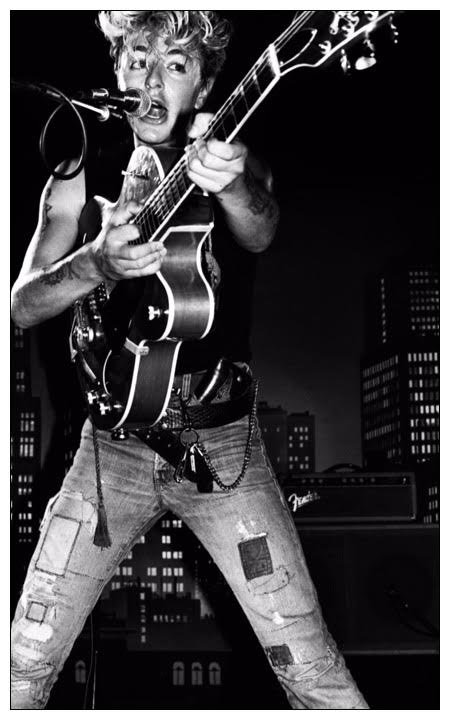

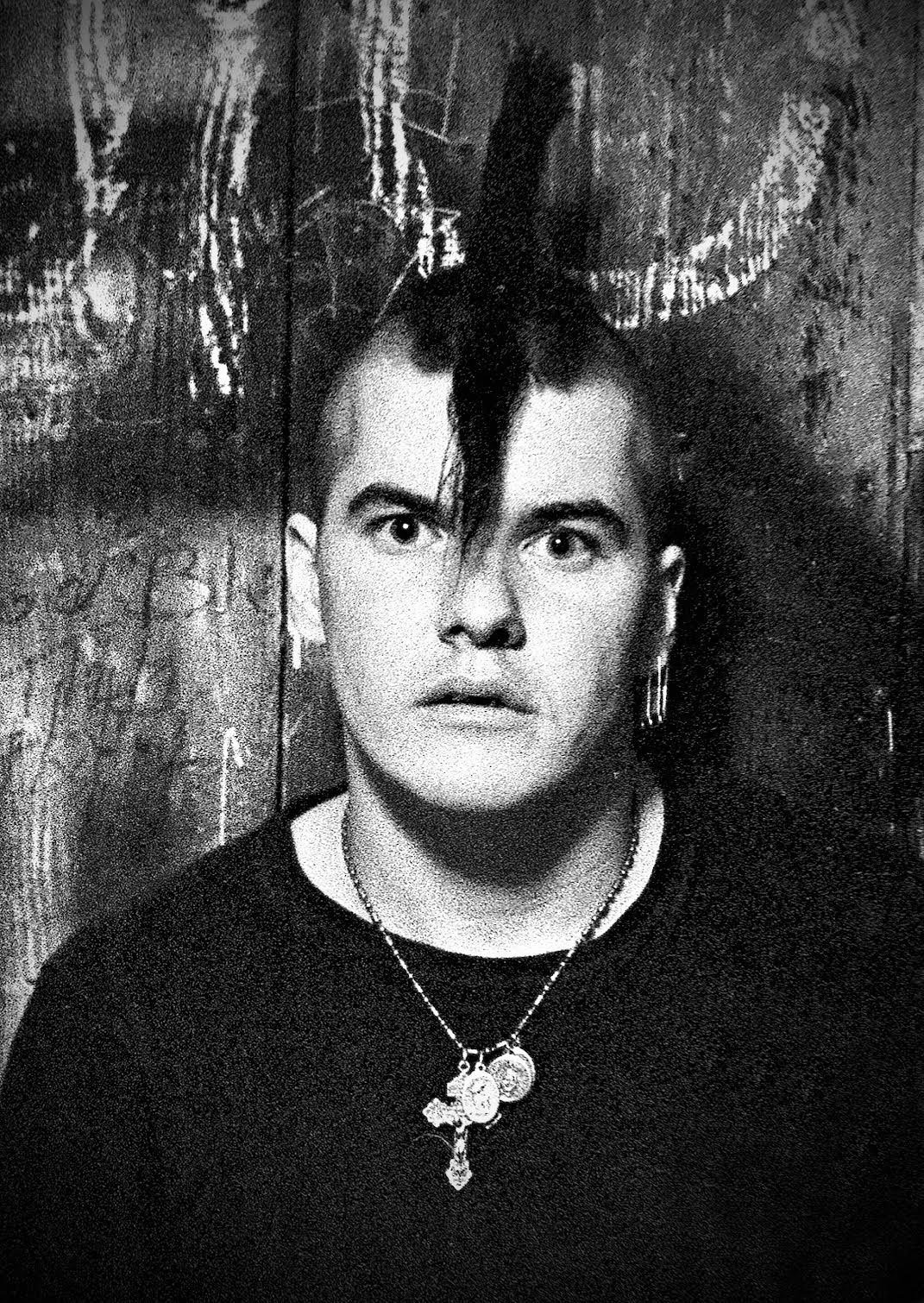

Stiv Bators of the Dead Boys, shot backstage at the Whisky, Los Angeles, CA, 1979. Photograph by Edward Colver.

And yet, as promising as it seemed at its inception, the potential of the first wave of punk was all but exhausted by 1978. New York-inspired British bands, such as the Sex Pistols and the Clash, had taken America by storm. The commercial success and media recognition they achieved were immensely larger than those of their New York counterparts, whose fame was quickly becoming eclipsed. The homemade roots of punk were commercializing rapidly both in the states and in Europe, but a group of frustrated suburban adolescents with a knack for punk were planning something unprecedented in the omnipresent heat of southern California.

As the American political pendulum swung further and further to the right in the late 70s, youth across the country got more and more fed up. The children born in the last few years of the baby boom and the first years of Gen X were raised on the myth of the 60s; many of their parents had been part of the counterculture, and the music played by these parents preached message after message of peace and love.

But peace and love weren’t what those kids got. They watched in horror as the Vietnam War ended in chaos, Ronald Reagan rose to power, and crime rates skyrocketed in big cities. Adults who had supposedly espoused the idea of sticking it to the man during the Nixon years were now complacent at best while the government became increasingly Republican. It was clear that no matter how many times someone listened to Buffalo Springfield or how many times they dropped acid, 60s counterculture hadn’t done its job. It was time for a change, and that change was hardcore punk.

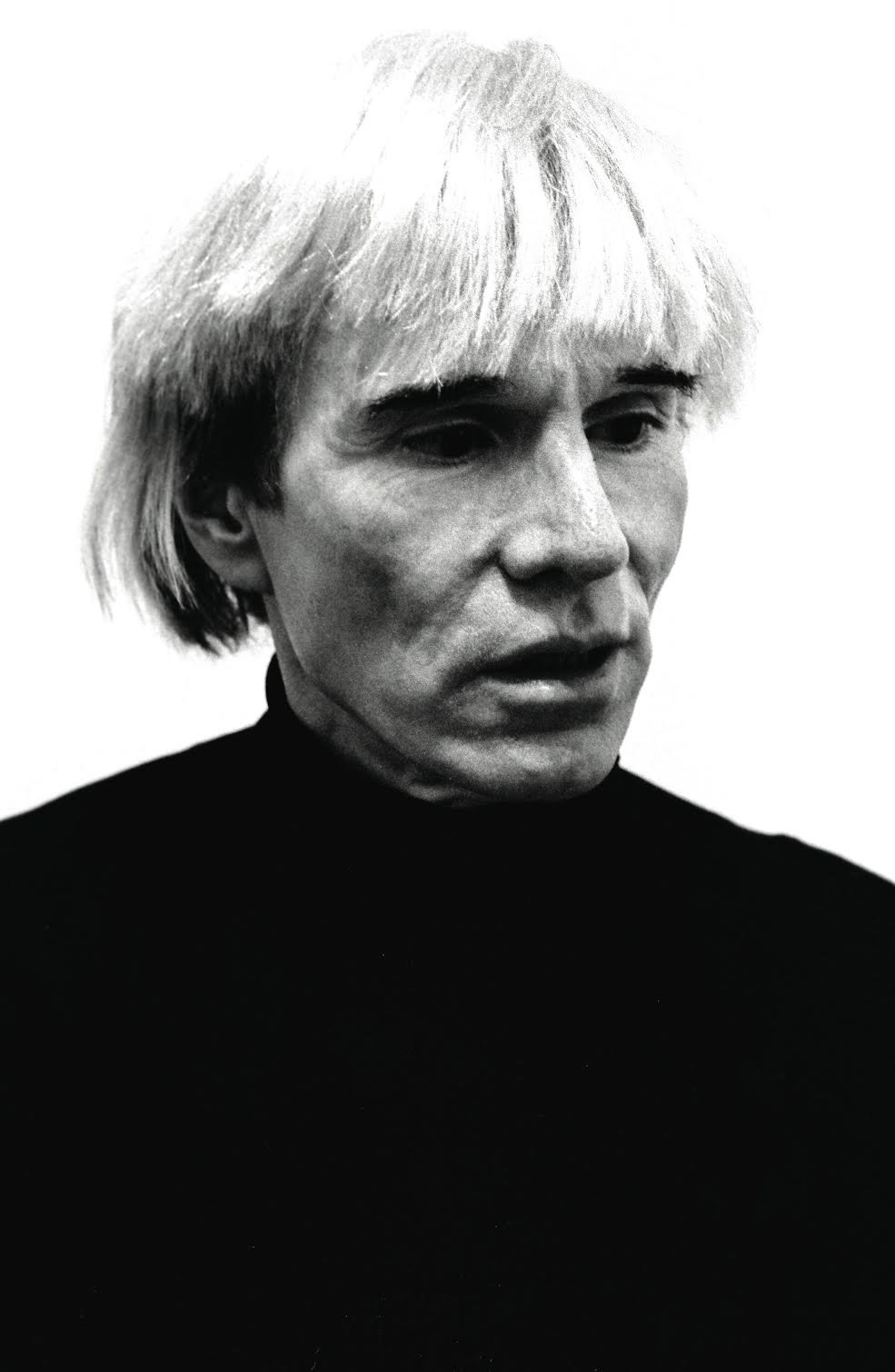

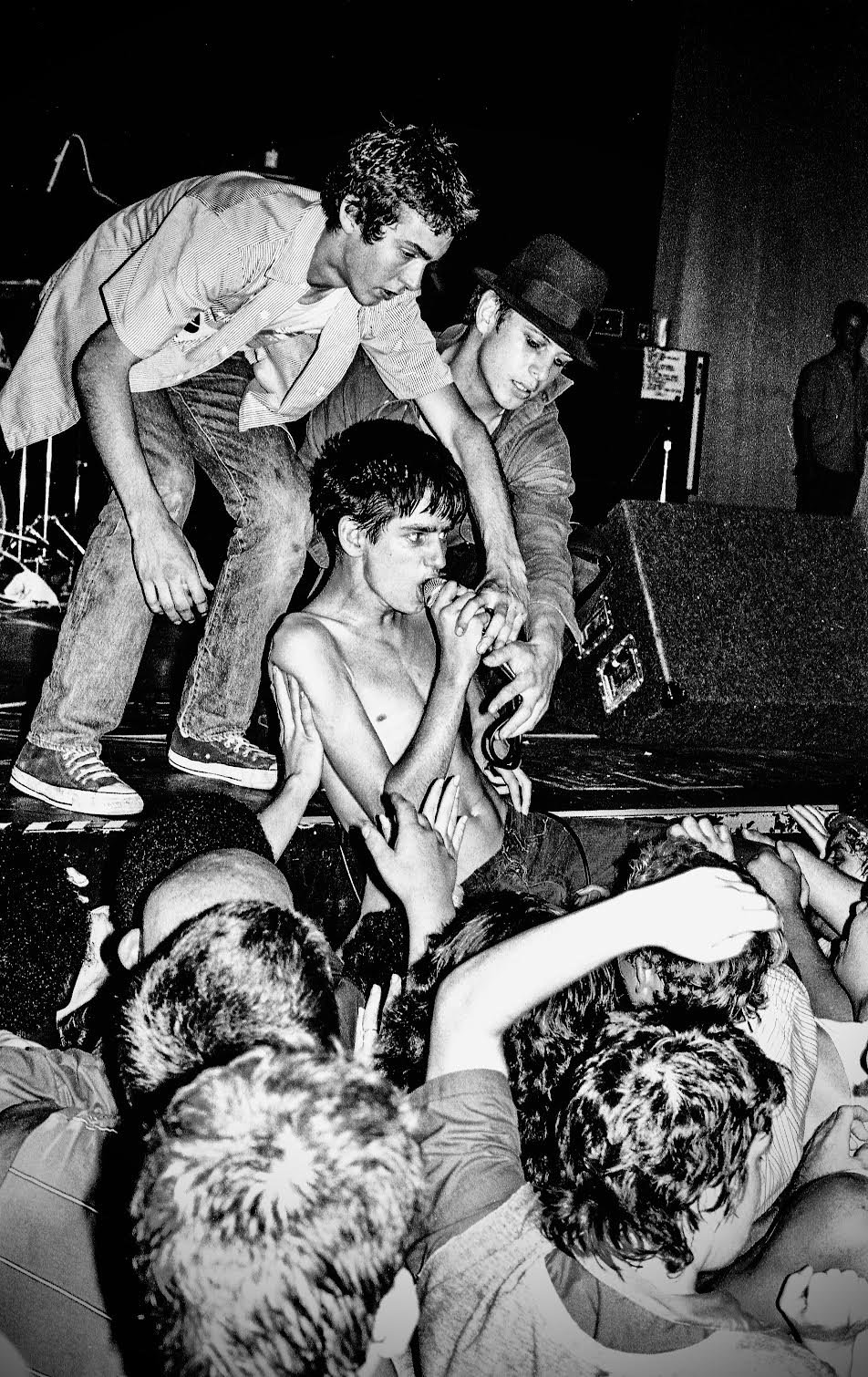

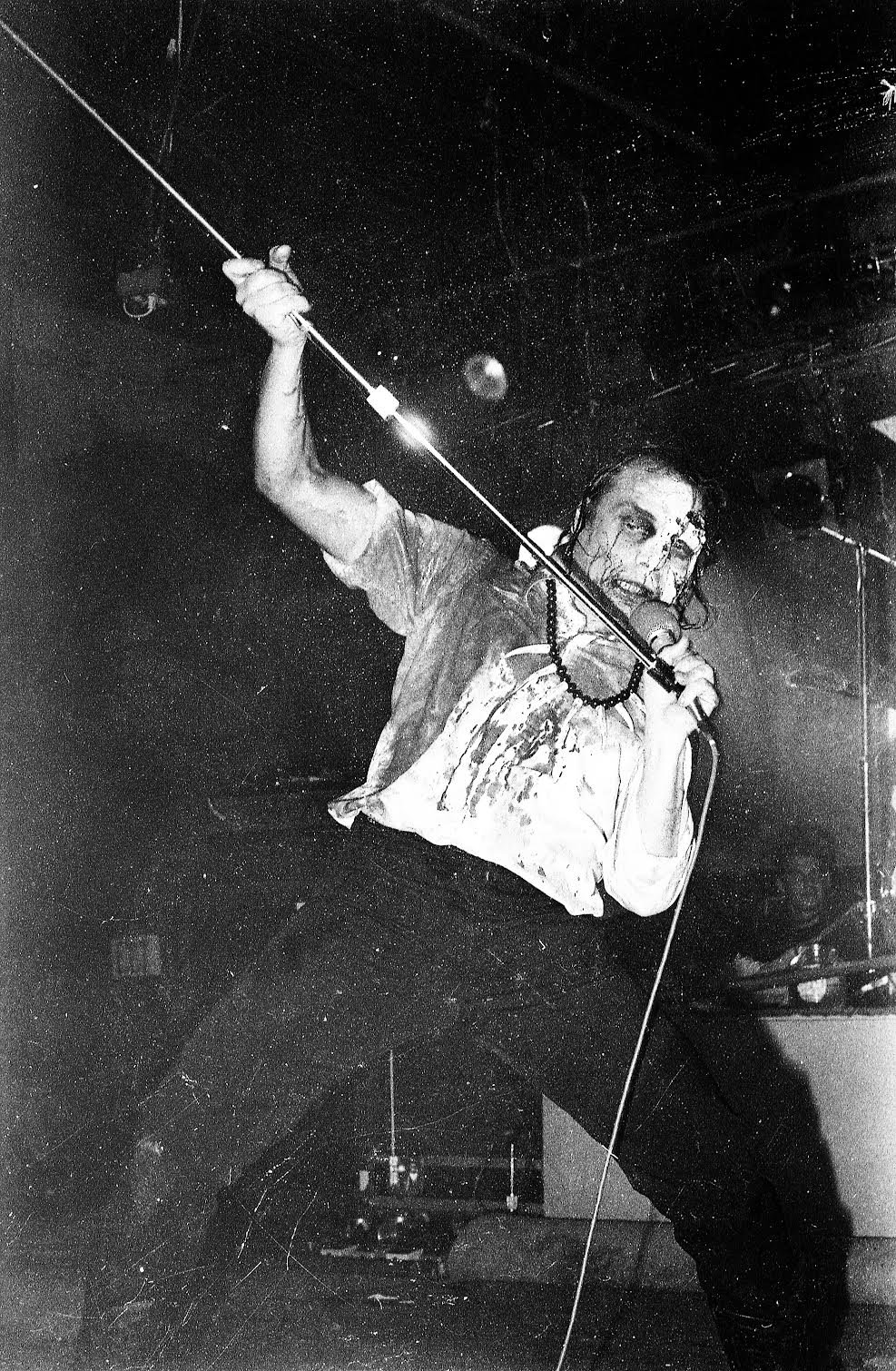

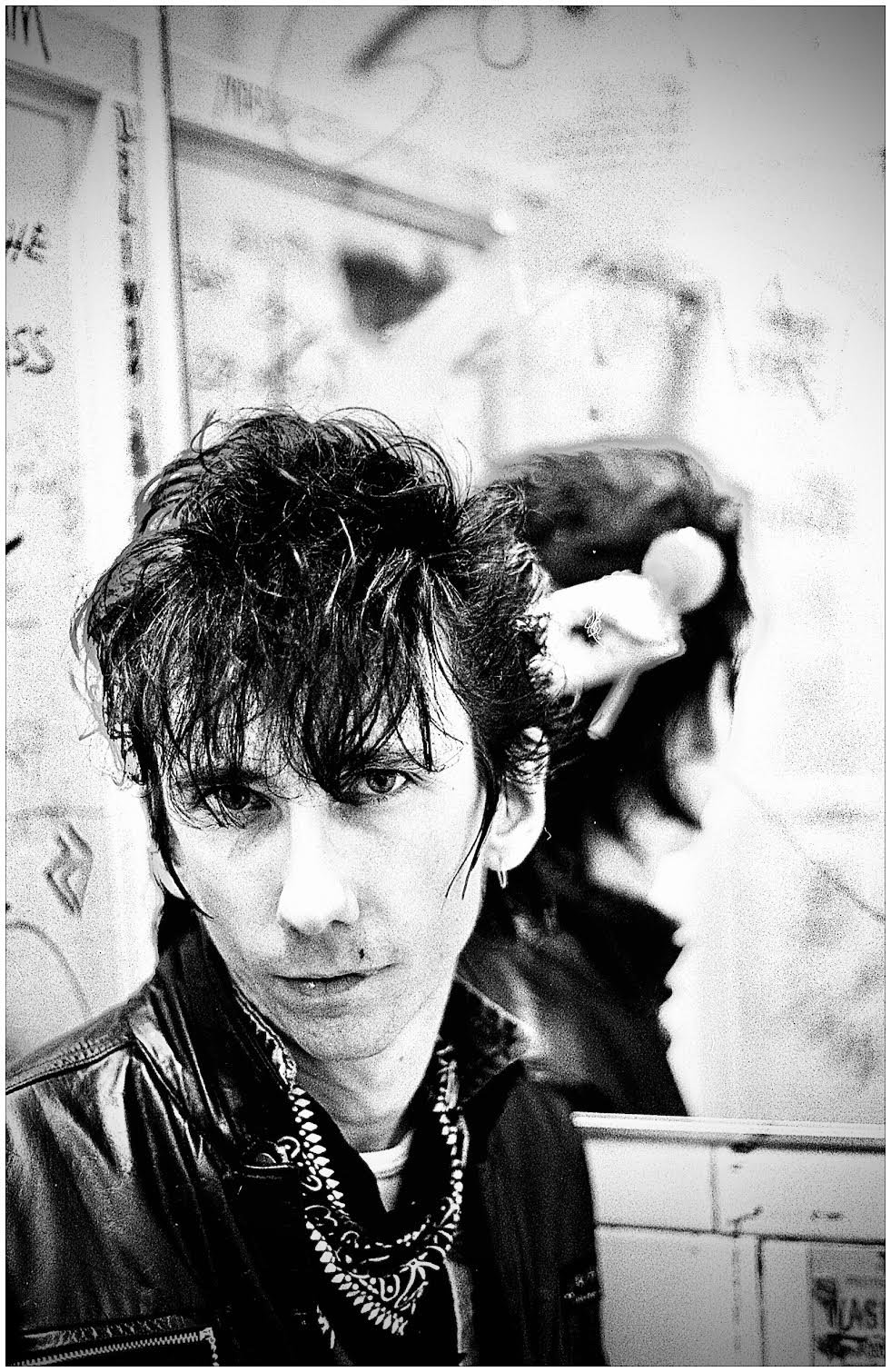

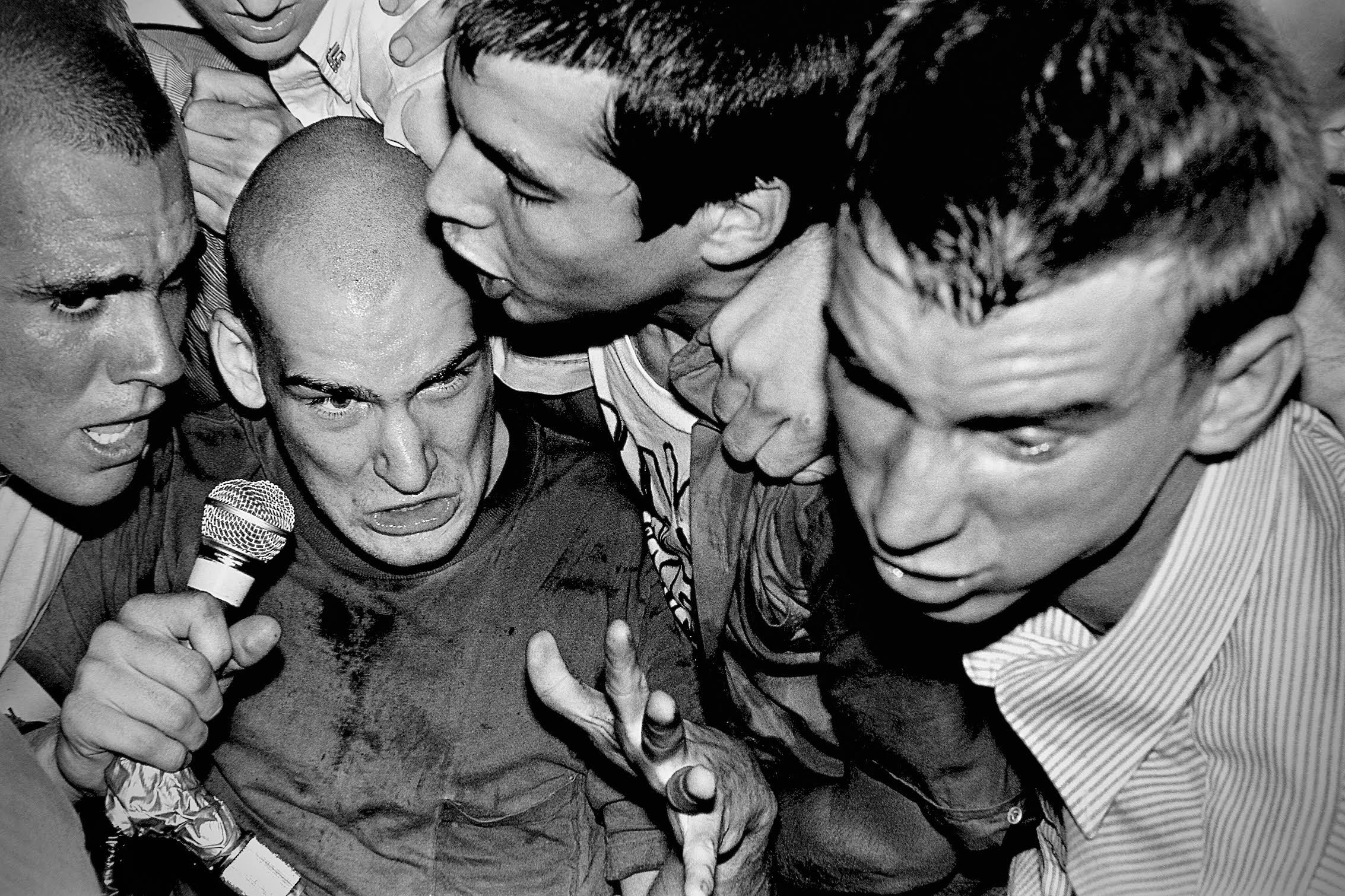

Darby Crash of the Germs, backstage at the Starwood, West Hollywood, CA, 1980. Photograph by Edward Colver.

Spearheaded by what was essentially an extended clique of pissed-off teenagers, California’s nascent hardcore scene gave the world its first taste of how brutal punk could really be: “Evolution is a process / Too slow to save my soul / But I’ve got this creature on my back / And it just won’t let go,” yowls Germs frontman Darby Crash on “Manimal,” released on the band’s 1979 album, (GI), arguably the first true hardcore record. The Germs were accompanied in rage and primitivism by the likes of the Dead Kennedys, Wasted Youth, Fear, the Circle Jerks, and Black Flag, whose music was dominated by distorted guitars and hellishly quick drums. Black Flag bassist and co-songwriter Chuck Dukowski was asked in a 1980 interview, “How come the songs are so fast and short?” Dukowski, clutching a giant bottle of Colt 45, responded with, “They’re fast because that’s what gets us off, okay, that’s the energy level. And they’re short because that’s how long the inspiration lasts.” When Black Flag guitarist, primary songwriter, and overall leader Greg Ginn was asked about the meaning of his band name in the same interview, he gave a slightly more concise answer: “Uh, it means anarchy.” Dopey and cliche as Ginn sounded, Black Flag truly operated like an anarchist cell; they lived in the basement of an abandoned church in Hermosa Beach, lost more money than they made putting out records, and oftentimes had to run from the LAPD at their vicious live shows. Dukowski’s explanation for the brevity of Black Flag’s music probably rings true for most of their hardcore contemporaries — hardcore songs seldom breached the two-minute mark and “full-length” albums were often no longer than twenty minutes.

Hardcore had its unforgiving sound nailed down. It had the police and the corporate rock hegemony to crusade against. It had legions of angsty, beer-chugging young fans who relentlessly moshed at shows and created fanzines to spread the punk ethos across the country. And yet, it was all but missing the crucial element of photography, which was too expensive to efficiently produce and disseminate through the scene. Flyers for shows were almost always devoid of photos and primarily consisted of cartoons and handwritten details. Album sleeves that featured photography only showed headshots of the band, failing to capture the power and chaos of their performances. Fanzines were actually full of photos, but their need to have a relatively large production level while maintaining the lowest possible budget resulted in these photos being incredibly grainy and their subjects unrecognizable. If hardcore were to succeed in avenging the death of the first wave of American punk, it needed ferocious photographs to match its ferocious attitude.

Enter Edward Colver.

Edward Colver was born in Pomona, California, in 1949. After being raised on the psychedelic music of the 60s, Colver began shooting photos in 1978 as the hardcore scene emerged from the once-sleepy suburbia around Los Angeles. Mere months after he began aiming his lens at the unruly punks overtaking renowned clubs like the Whisky a Go Go and the Hong Kong Cafe, Colver had his first photo published in BAM magazine: an action shot of performance artist Johanna Went. As the community around hardcore grew and developed, live shows became much more chaotic and even violent. An intrepid few were game enough to venture into the world’s first mosh pits with camera equipment, and Colver did just that. In fact, Colver appears at the foot of the stage in a rare 1983 video of Black Flag — standing steadfast as the sole photographer in a churning mass of 3,000 rowdy punks.

Edward Colver’s visual work remains among the most legendary and iconic in punk history. The bare-chested, muscled punk frontmen that serve as the focal points of many of his images have an air of neoclassical dynamism about them, making Colver seem like a sort of punk Jacques-Louis David. If the band played between ’78 and ’84, chances are he captured their animosity for the ages. Colver also took scores of album covers for the bands he went to see — some of the most well-known include the Circle Jerks’ Group Sex (1980), T.S.O.L.’s self-titled EP (1981), Black Flag’s Damaged (1981), and Bad Religion’s How Could Hell Be Any Worse? (1982). The equipment Colver used for these shoots was fittingly simple for the homemade vision hardcore espoused. Colver was gracious enough to take some time to talk to me over the phone and told me that, in regards to his gear, “I had nothing special, a 35mm camera, and I had a 50mm lens which is akin to human vision perspective — it doesn’t distort, it’s not long or short or a wide angle or anything. It’s just what you see.” It seems as though the video footage of Black Flag is representative of much of Colver’s experience in the pit. In spite of all the frenetic stage diving, perilous pits, and angry fans spitting on band members, Colver emerged from almost every show virtually unscathed.

Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat, Alpine Village (aka The Barn), Torrance, CA, 1982. Photograph by Edward Colver.

Jello Biafra of the Dead Kennedys, Florentine Gardens, Hollywood, CA, 1983. Photograph by Edward Colver.

And yet, although he might come across as the Moses of hardcore, parting the rough seas of the Santa Monica Civic Center to get his photos, Colver has largely moved on from his days as an icon of the LA scene. I asked him what the best concert he attended was, expecting to immediately hear the names of a few of my favorite 80s hardcore outfits, but instead was met with: “I’ve seen a bunch of amazing shows. I saw the Mothers in 1966 when I was 16, stuff like that. But probably one of the best punk shows that I had seen was, well, the Dead Kennedys at the Whisky. And MDC and the Dead Kennedys and Minor Threat at The Barn in ’82 was a memorable night.” Colver is so unabashedly proud of the psychedelic and experimental music he grew up on that Frank Zappa and the Mothers come to his mind before that amazing show at The Barn. And it didn’t end there. When I asked him about a concert he missed and regrets not attending, Colver thought for a second before telling me: “I was kind of already out of David Bowie by the time he came and performed as Ziggy Stardust in LA, and I didn’t go to it because I was kinda already losing interest, haha! I wouldn’t have photographed him back then, but that’s one of my concert regrets.” Proud Zappa and Bowie fan as he is, Colver didn’t hesitate to give a hot take on Bowie’s output: “I like his early stuff. His later stuff is garbage, like Let’s Dance. It’s horrible s—!” I’m inclined to agree.

As our conversation progressed, I was hit with surprise after surprise. One of the most earth-shaking ones came in the form of an incredibly nonchalant Colver telling me, “I grew up listening to heavy psychedelic music and underground music in the 60s, and I still listen to a lot of that. I really like it a lot. It probably pisses people off that I don’t listen to punk rock. It’s way too aggro. I can understand it and I loved it back then, I don’t listen to it at all nowadays.” Oh my God, I thought, Edward Colver is so punk that he doesn’t even like punk! Still, he remembers the early days of his live shoots fondly. Colver’s 1978 live shot of performance artist Johanna Went used by BAM magazine was the first of his photographs to ever be published, and it was by pure chance. When he recounted the story, Colver lit up: “That was really cool! It was like, ‘Wow, this is exciting, how neat!’ It was a total fluke … some friends invited me over and said ‘Hey, we’ve heard you’ve been taking photos, bring some,’ and I was like ‘Okay.’ And it turned out that Blair Regan[’s] sister and her husband were editors at BAM magazine, and they saw my picture of Johanna Went and were like, ‘Oh, we’re doing a story on her! Can we use this?’ and I was like ‘Yeah, sure.’ So just a few months after I started shooting photographs I got one published, and that was real inspiring.”

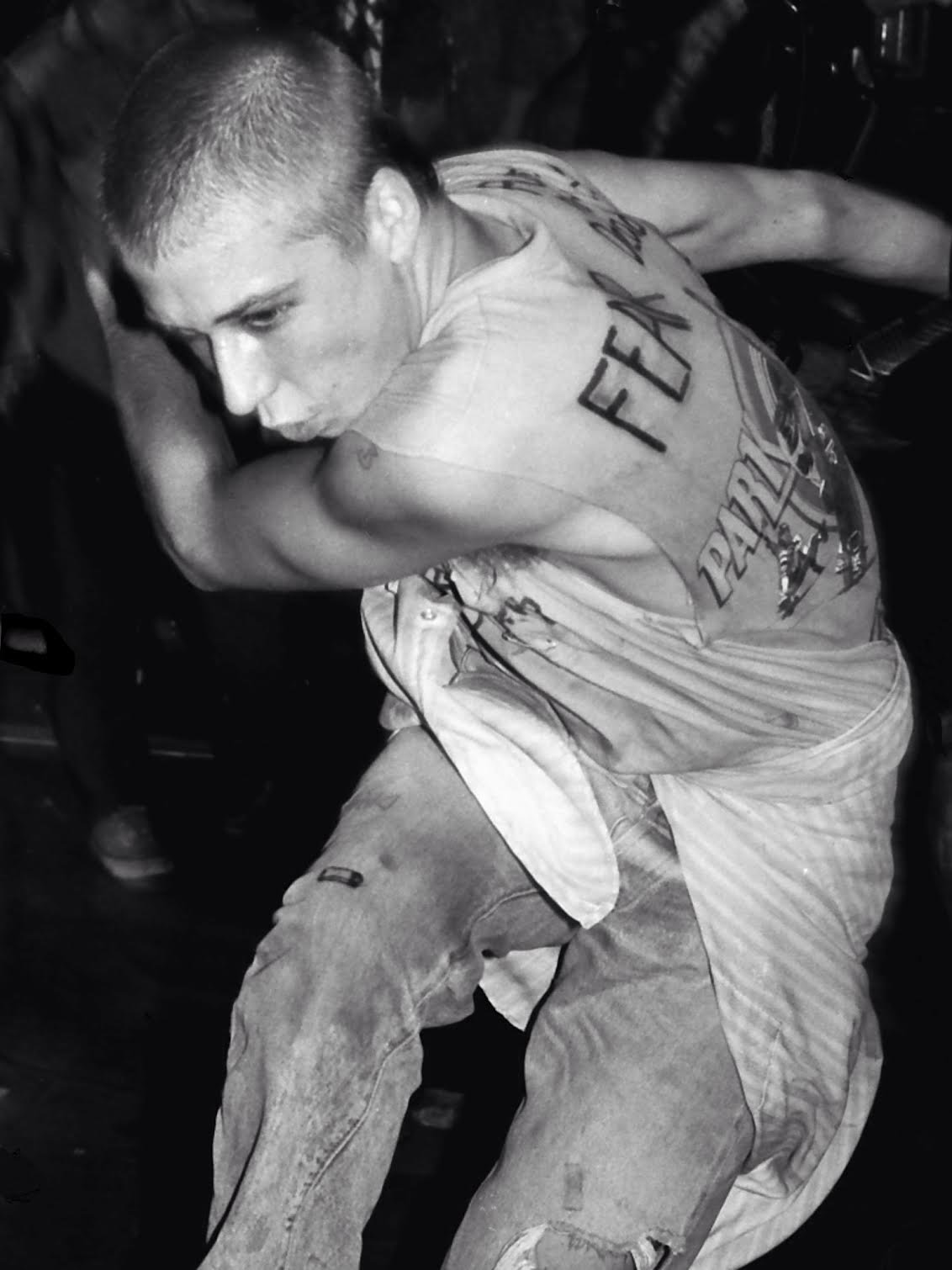

Henry Rollins of Black Flag, black & white photograph from the Damaged LP cover session, Hollywood, CA, 1981. Photograph by Edward Colver.

Something that set Colver apart from many of his contemporary visual artists within the scene was his willingness to experiment. When he shot the cover for Damaged — a harrowing image of Black Flag frontman Henry Rollins punching a mirror and bleeding — he didn’t just shoot what he saw, but he orchestrated the entire composition of the artwork:

“The ‘blood’ on the Damaged cover is red India ink, powdered instant coffee for consistency and color, and liquid dishwashing soap for consistency. It wasn’t just coffee and red ink. Yeah, I experimented at the Oxford house after I set up the mirror. I covered the back with duct tape, washed the front of it, then struck it once with a hammer, turned it back over, cleaned it again and then I went in the kitchen and started experimenting with the red India ink that I brought. Nowadays you can get stage blood 24/7, 365 but back then it’s like, f—, I didn’t know where to find that stuff. It was probably only available at prop houses, which I didn’t frequent. So I made it.”

Sadly, Colver’s remarkable innovation as seen on the original vinyl copies of Damaged can’t be seen on more recent pressings. “It’s so embarrassing and so aggravating, the ridiculous, garbage reissue covers they’ve done of it.” Colver said. “I don’t understand it. They add black and white and washed out color, and this isn’t what I shot, you know?” Damaged, along with every other release in Black Flag’s catalog, is owned by the notoriously stingy indie label SST Records. Colver has no say in how SST’s new copies of Damaged turn out looking, but thankfully, the version of Damaged available on streaming platforms features the original cover the way Colver intended it to look.

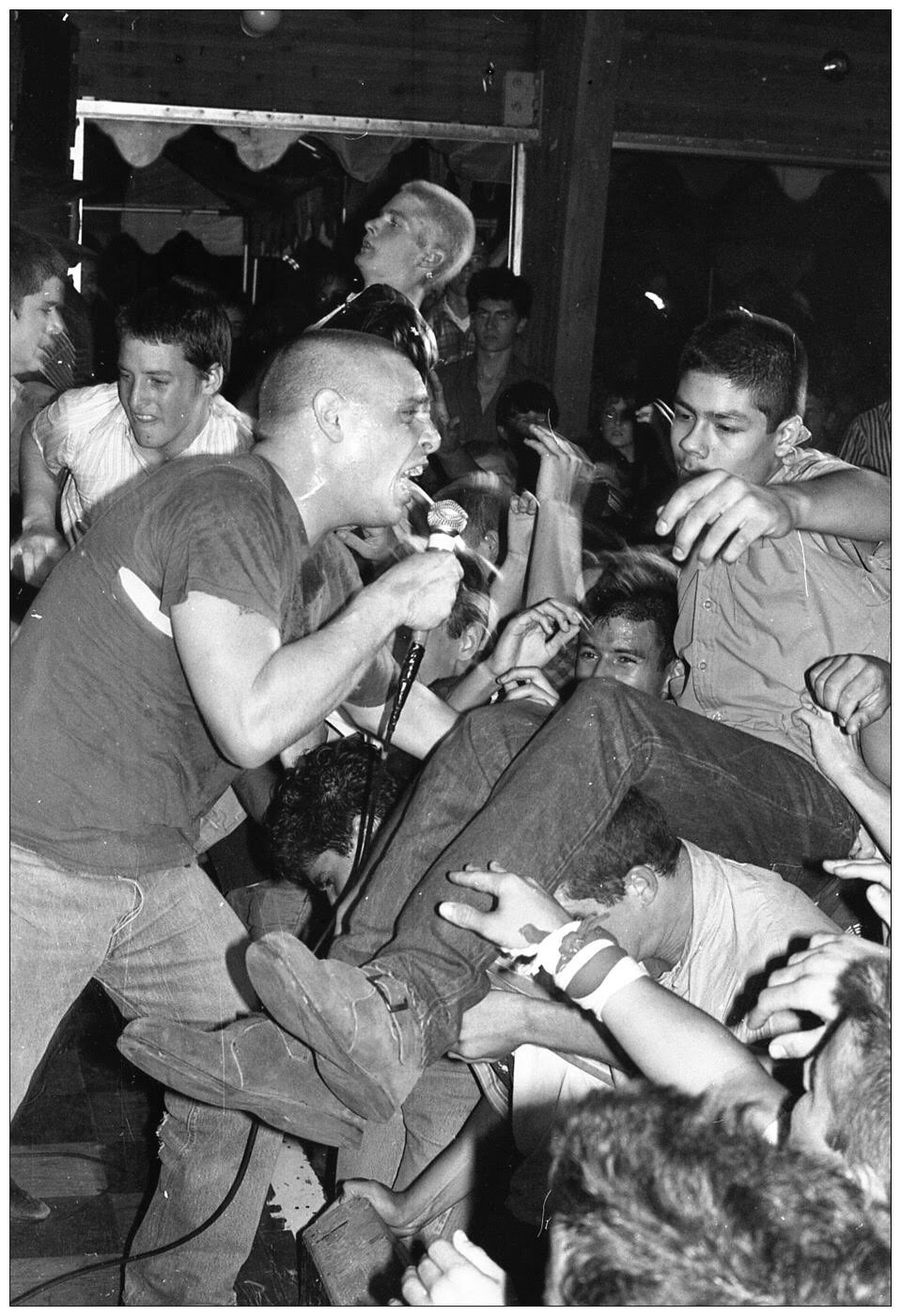

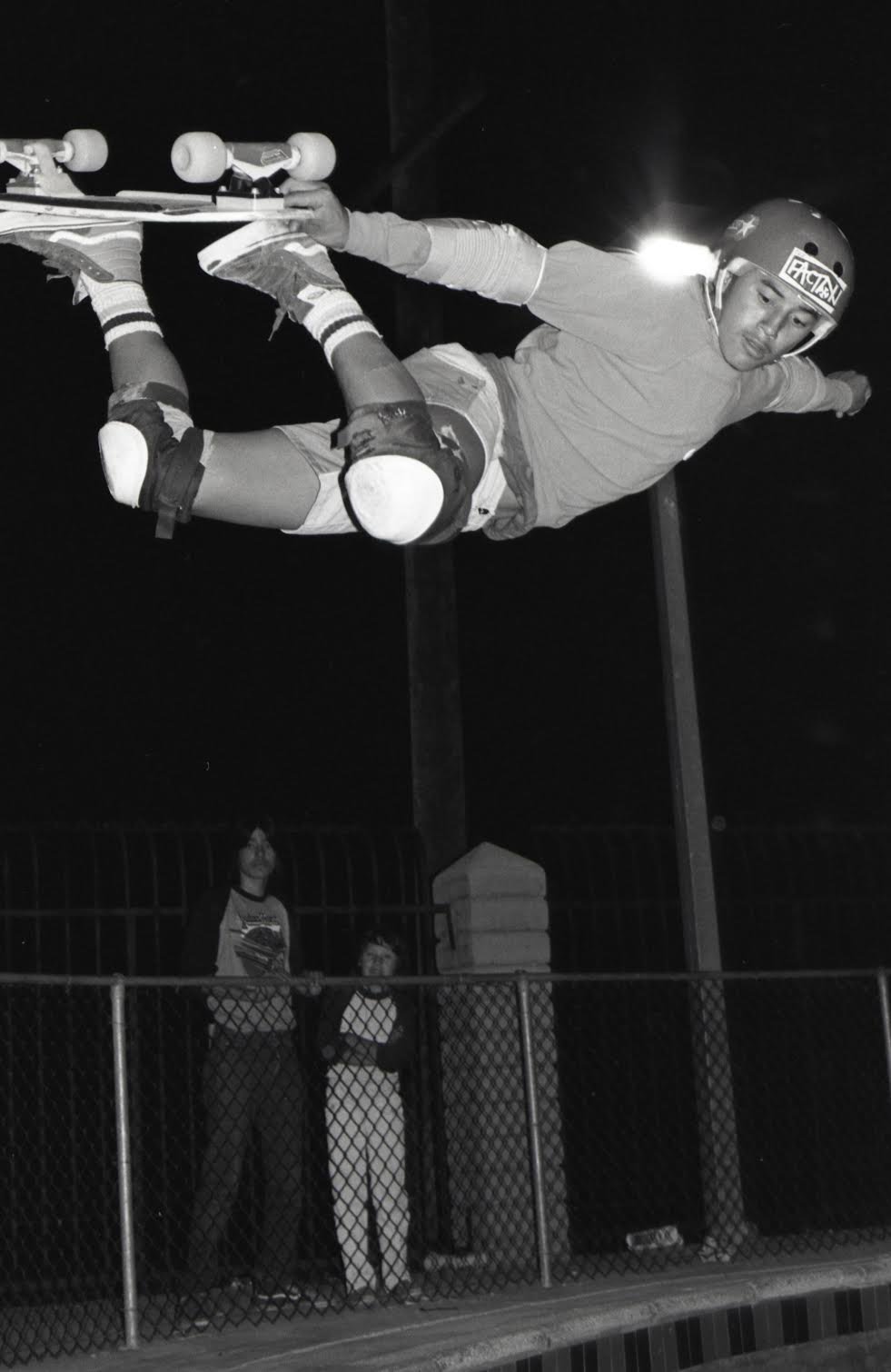

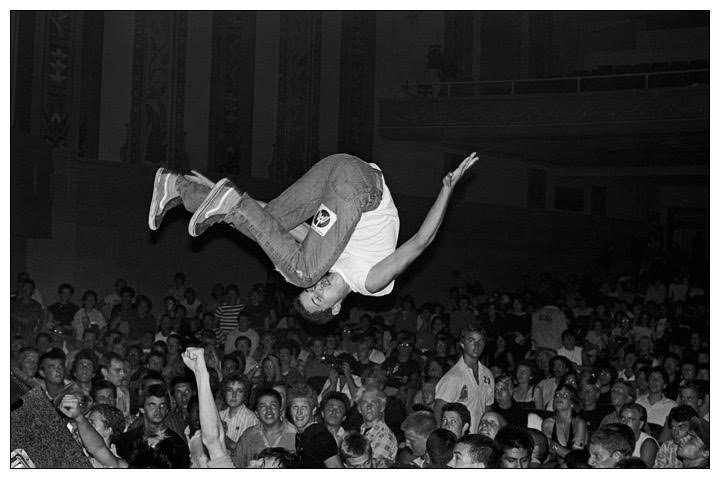

Skateboarder/punk Chuck Burke doing a forward flip stage dive at Perkins' Palace, Pasadena, CA, July 4th, 1981. Taken at a D.O.A., Adolescents, and Stiff Little Fingers show. Shot during the Adolescents' set. Photograph by Edward Colver.

One of Colver’s most renowned images shows LA skater Chuck Burke doing an impressive flip off the stage and into the crowd at a 1981 show featuring Irish punk pioneers Stiff Little Fingers, SoCal mainstays the Adolescents, and the best-ever Canadian band, D.O.A. (sorry, Rush). The imagery and composition of Colver’s “flip shot” was borrowed by Playboi Carti for the cover art of his 2018 debut album, Die Lit. Thanks in part to its cover, Die Lit was a wakeup call for me — I had never really enjoyed trap as a genre, but seeing a familiar image from a genre I loved being given a new context convinced me to give Carti a shot. I was blown away. The quickness and aggression of his songs made it seem to me like he was paying homage to punk. After I did a little digging, that homage became crystal clear; Carti’s a fan of the Circle Jerks and Black Flag, and he even has a Bad Religion tattoo on his stomach. He sees himself as a punk too!

During our talk, I asked Colver about his thoughts on Carti and Die Lit. Like any veteran of early punk, Colver doesn’t shy away from speaking his mind, and Carti’s take on the flip shot just didn’t impress him: “Somebody posted my alternate photograph of Chuck Burke stage diving where it’s a vertical photograph and one of his feet’s cut off in the frame. And they had posted it up and tagged me, and then I went on there and everybody was going ‘Oh, [Playboi Carti]’ and it’s like, what the f— are you talking about? … Why would they even say [Playboi Carti]? That’s obviously an old photo and it has nothing to do with that artist.” Colver continued, “A friend of mine found the post on that and went ‘Hey, it said this guy did a great job of sourcing the photograph.’ You mean you finding my ubiquitous, iconic photograph of a stage diver? … It even said in the thing it was shot in a studio in Highland Park [the LA neighborhood, not the city in Illinois], and I’m sure there’s more than one Highland Park, but I live in Highland Park. Did they attempt to recreate my photo right here in my town, even? It blows my mind.” I see where Colver is coming from. Carti wasn’t trying to rip Colver off, but he’s never acknowledged Colver’s work even though Die Lit’s cover is clearly inspired by his photography. Most of Carti’s young fanbase is probably unaware of hardcore at large, let alone a singular photo from the hardcore scene, but it doesn’t matter. Carti should give credit where credit’s due. Knowing how strange and mercurial the rapper is, though, the likelihood of that happening is unfortunately pretty low.

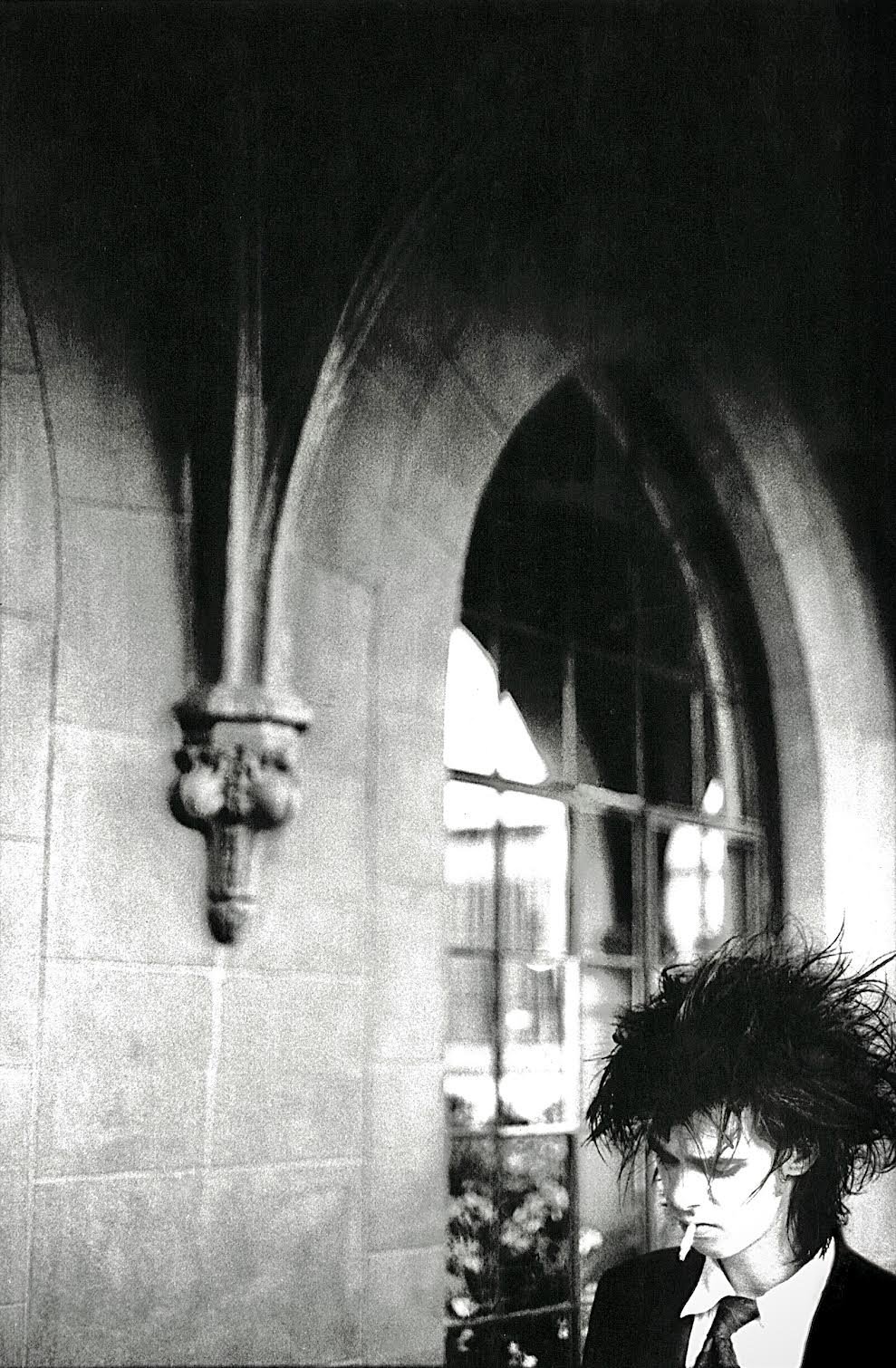

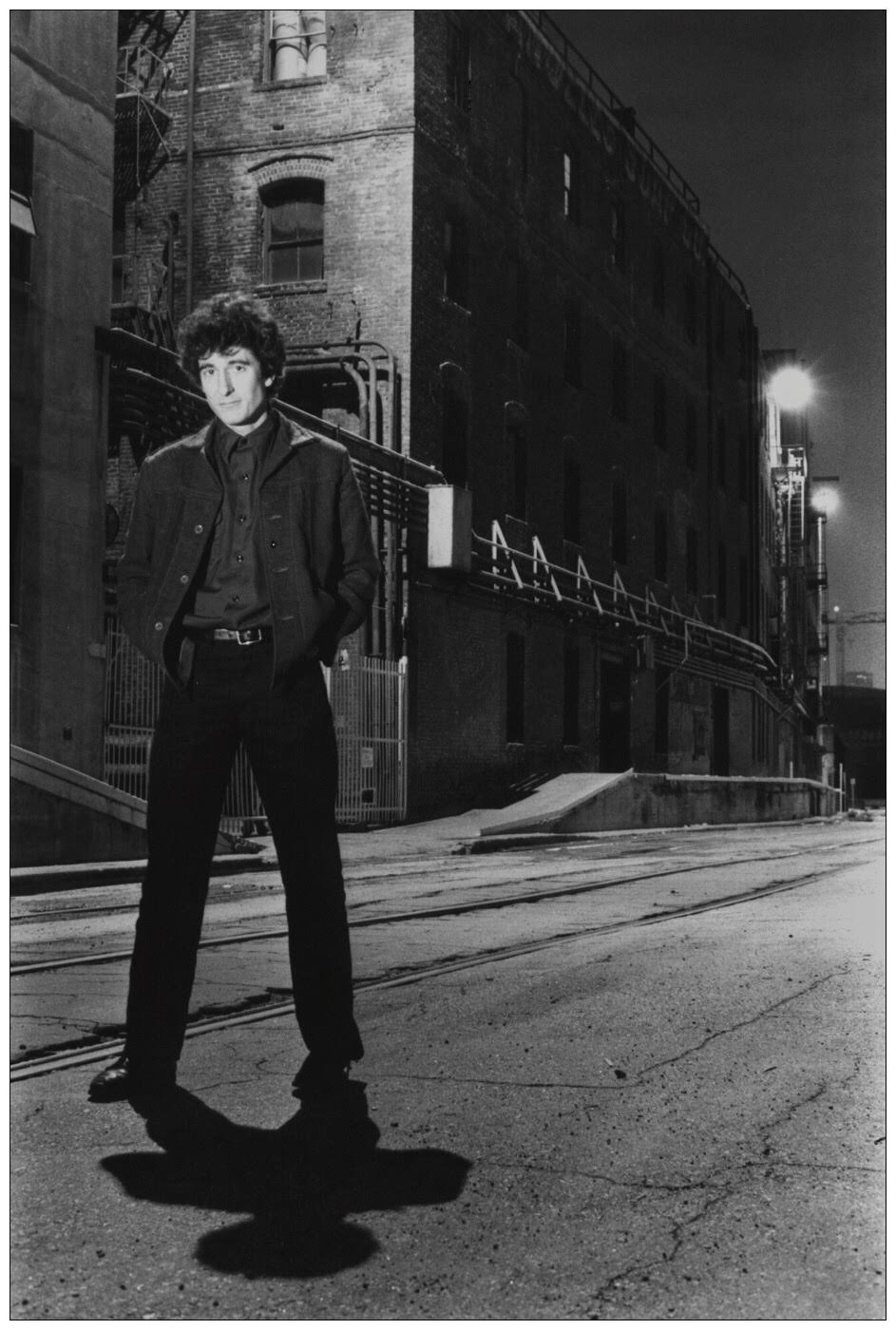

Nick Cave photographed on the porch of the Chateau Marmont, West Hollywood, CA, 1985. Photograph by Edward Colver.

Ice Cube just after NWA broke up. From Colver: "I honestly shot this in one minute, just after I shot press photographs of him signing a contract with Priority Records. I shot two polaroids, did not look at them, had him put his chin down, and then shot ten black-and-white photographs on 120 film with a medium format camera." Photograph by Edward Colver.

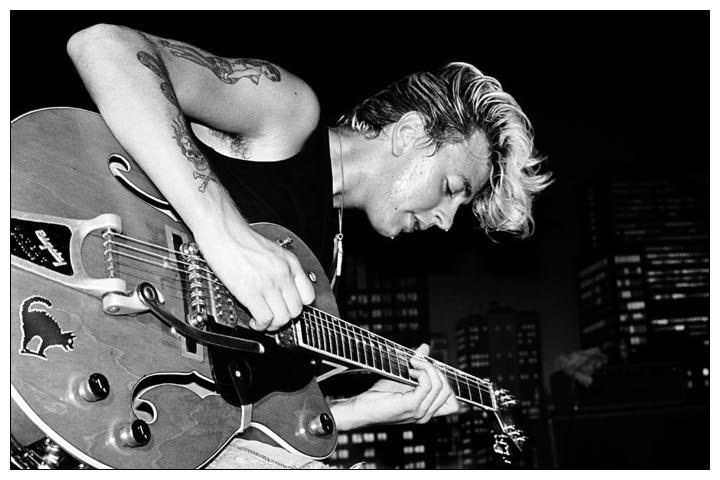

With the rise of thrash metal in 1984, Colver decided to retire from live photography. “Thrash bands started up, and it was like, ah, no thanks,” he said. “And I got a studio and started working for record labels that actually paid me, which was a fluke. I’ve still got two bounced checks from [defunct indie label] Posh Boy for a hundred bucks each. I really enjoyed it, it was an entirely different experience. I ended up with 2400 Speedotron heads, five lamp heads, expansion booms, and all kinds of stuff. I rocked the hell out of that stuff, I was really good at what I was doing, and it was really fun.” Though Colver’s methods and equipment changed with his shift to studio work, his photos never lost their radiance. Colver’s scope grew beyond hardcore, and everyone from Nick Cave to The Red Hot Chili Peppers to Ice Cube began to feature in his work. He even had a studio shoot with Andy Warhol. Even though his musical scope and artistic execution expanded, Colver’s vision remained the same: “No photographers [inspired me] when I started shooting. I was schooled in applied arts, and that’s why I have a concept of composition in my photos that I don’t think most people that deem themselves to be a photographer have. Maybe they’re taught how to use a camera and this and that, but they aren’t schooled in proportions and balance and composition in photos. I would be in a pit and it’s nothing to just take a photo in the chaos, but I tried to compose it, and I think it shows that I had that background in my work.”

For the most part, actively shooting photography is a thing of the past for Edward Colver today. When asked about what keeps his visual creativity going, he said, “Working on my yard, hahaha! I don’t know. I shoot photographs a little bit nowadays, not much, mainly for old friends and stuff.” And in an age when the phone camera has given anyone and everyone the ability to shoot shows, Colver still prefers the formula that made his work so good in the first place. “I never shot with a digital camera, and I’m not really interested,” he said. “I shot film, now it’s termed analog. … I don’t necessarily belittle digital photography, but at the same time it’s like, good Lord, it’s so different and accessible. When they initially came out, there was always that dwell time. I’d watched people, you’d hit a button, and it would go tick-tick-tick, snap! The photo was long gone! I would never even dream of shooting with one of those cameras. … Now they’re instantaneous, so it’s really changed, and the resolution’s okay.”

Music photography today may be far cry from what it was in the days when Colver braved the glass-littered pits and drunken attendees of punk shows, but he still loves to talk and interact with people over Instagram, which is how I initially got in touch with him, and how tens of thousands of people show Colver their love for what he did. Scrolling through his feed, Colver’s posts are commented on by everyone from old comrades like T.S.O.L. singer Jack Grisham and Circle Jerks guitarist Greg Hetson to everyday fans like myself. Colver loves showing his photos to the world, and he of course has a touch of punk cynicism to add on to his online presence: “I’ve got, you know, followers and fans on Instagram and stuff, and they said ‘Oh, come out and bring your camera!’ I stopped that s— almost 40 years ago! It’s really funny, they think I still do it, and I’m not interested, and it’s rather a vanquished job.” Perhaps the glory days of music photography are long gone, but Edward Colver is still around to show people what it was like to really be there, and every single photo he took is a testament to his genius.

The author wishes to thank Edward Colver profusely for making this interview happen, being generous enough to handpick photographs to include in this piece, and contributing the captions for each photograph used. You can follow Edward on Instagram @edwardcolver, like his official fan page on Facebook, and check out his website edwardcolver.com to see more of his groundbreaking work.