Encountering Intersubjectivity: Abstract Physicality in “That Smell” by Sonallah Ibrahim and “Untitled (1965)” by Samir Rafi

Diana Deng - June 18, 2023

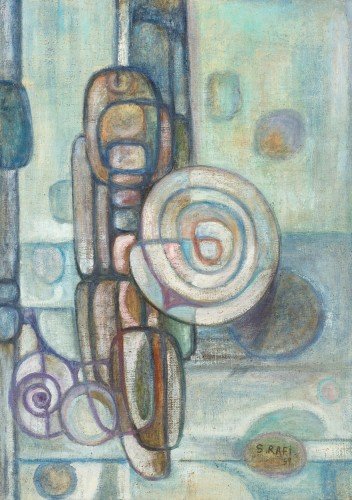

Figure 1: Samir Rafi, Untitled. 1959. Oil on canvas. Barjeel Art Foundation.

In the 1960s, disillusioned by the failed promises and relentless persecution of the state, many Egyptian artists and writers returned to the individual—whose figure became elusive amid the prevailing discourses on the collective—in search of a truthful representation of society. Past scholarship has considered the subjectivity evoked by this individualist approach as an antithesis of the collectivism imposed by the state. By comparing Samir Rafi’s painting Untitled (1965) and Sonallah Ibrahim’s novel That Smell (1966), I will suggest another way to understand the relationship between the individual and the collective by focusing on the abstraction of the body and the intersubjective space it engages in imagination. Completed under the Nasserist regime, both the painting and the novel reflect the socio-political circumstances in which they were produced. Both the painting and the novel objectify the individual into abstract body parts, which are in turn employed to embody the unrecognizable and inaccessible whole. They create an imaginary intersubjective space in the perception of abstract physicality, which mocks the metonymy of statist Pan-Arabism, which involves brutal appropriation and false representation of the individual in the name of unity. While revealing the inherent deficiencies of the statist rhetoric, the two works suggest a different possibility of unity among Arab people in the intersubjective space. Instead of fabricating collective symbols, this approach relies on a shared epistemology derived from the perception of abstraction.

In October 2003, the speech given by Egyptian writer Sonallah Ibrahimon at the ceremony of the Arab Novel Award shocked the country. Instead of expressing his gratitude, Ibrahim uncompromisingly attacked the Mubarak regime. He undauntedly pointed out that it was his obligation to reject the prize “awarded by a government that lacks the credibility to bestow it”1. This legendary speech brought back the distant memories of a time in which Ibrahim’s critical attitude and deep sense of mistrust of the state took shape—a time in which the state was still in its heyday of power and influence.

In 1960s Egypt, statist politics prevailed in every corner of the country. “Concerned with order and intolerant of independent forms of power,” the state repressed, incorporated, and, in some cases, violently eliminated all the popular mobilizations, political parties, and literary movements that took place on its territory.2 While many intellectuals at the time—either co-opted by the state or genuinely believing in the power of solidarity—endorsed its “interventionist and patriotic” version of Pan-Arabism, some Egyptian writers and artists remained alert to this monopolized ideology, whose rhetoric substitutes “collective liberation” for individual freedom and glosses over the distance between a unified state in conception and a diverse political community in reality.3

Among these vigilant intellectuals were the novelist Sonallah Ibrahim, then young and ambitious, and the painter Samir Rafi. Like many others who felt the impotency of statist Pan-Arabism and noticed the inherent deficiencies of its institution, they returned to the individual in search of a different way to approach the collective. In Notes from Prison, Ibrahim reflects upon the role of the artist who “must dive into the depths of the people” and indicate a direction of change,4 while suggesting that it is necessary to experiment with new forms to represent a reality that is no longer possible to capture “using old methods” 5. This formal experiment eventually took shape in his first novel That Smell (1966), in which, speaking in a simple and unliterary language, the first-person narrator adopts a minimalist approach to the outside world.

Similar to Ibrahim, Samir Rafi experienced a significant change in style in the years of Nasserist statism. Rafi was known for the surrealist approach in his paintings of Egyptian daily life, which “contain recognizable figurative imagery, with characteristic contour lines that connect one body with another” 6. However, he turned toward abstraction in his works created between 1959 and 1963, as exemplified in his oil painting on burlap Untitled (1959), in which the individual is radically abstracted into cylindrical and spiral shapes. Based on the experimental forms in Ibrahim’s novel That Smell and Rafi’s painting Untitled, I suggest that both of them objectify the individual into abstract body parts, which are employed to embody the unrecognizable and inaccessible whole. They evoke an imaginary intersubjective space in the perception of physicality that contrasts the metonymy of statist Pan-Arabism, which involves brutal appropriation and false representation of the individual in the name of unity.

Intersubjectivity remains integral to the perception of abstraction for many important artists and philosophers throughout Arab art history. In her letter “How the Arab Understood Visual Art,” Saloua Raouda Choucair considers abstraction as the process of distilling reality to its quintessence, which Arabs realize in imaginary visions (suwar) “more real than common reality” 7. Scheid suggests in her introduction to the letter that Choucair transforms Arabs into “cognizant, subjective agents,” which highlights their role in the meaning-making of visual objects.8 Drawing on Alhazenian optics, Scheid further notes that what Choucair suggests in the letter is an intersubjective way of knowing the world “through the interrelationship of forms” 9. For Alhazen, the ordered single form (al-sura al-muttahida) of a visual object “in its unified plenitude” is gathered by way of “spatial-temporal displacement” 10. In this process, imagination approximates and structures “the physicality of the visual object by way of an imagined form,” which is measured against a recognized universal form (sura kulliyya) in an effort to grasp its verified true form (al-sura al-haqiqiyya). 11 By contemplation aided by imagination, the universal form that points to “the eidetic essence” of a visual object becomes “accessible and designates the wholeness of that individual entity.12

Based on Scheid’s idea of the intersubjective, I consider intersubjective space as the imaginary space created by the spatial depth of perception and its horizons where “relations with others are opened up” 13. In this intersubjective space, the beholder engenders the collective, represented by the universal form that conjures up in imagination the wholeness of the individual entity through contemplation on its abstraction. In That Smell and Untitled (1965), the imaginary human figure constitutes the universal form of the visual objects’ abstracted physicality, whose essence lies in the individuality—the state of being a unique independent entity—of the human body in its integrity.

In That Smell, the intersubjective space is created with the recurring imagery of “the bare forearms” in the imaginary sexual encounters between the narrator and the women he meets. Unlike the rest of the short novel, the narrator provides detailed and sensuous physical descriptions for these encounters. The imagery of the forearms first appears in the narrator’s recollection of his first sex with Nagwa, his ex-lover. In the italic block quote of his inner psychology, the imagery of Nagwa’s “bare forearms” connects them spiritually through physical proximity:

We thought of nothing, feared nothing, and when my cheek brushed her cheek, when our noses touched, when our heads rested against each other, when our eyes stared at the same place on the ceiling, then nothing else had any importance. 14

At the moment, their distinct perspectives converge. They no longer see each other as body parts: they are connected to each other’s entirety. As the narrator’s thoughts travel back to the present, this imaginary spiritual unity is directly contrasted with the real-world circumstances in which Nagwa also bares her forearms, but their potential sexual encounter results in futility: “something [is] missing, something [is] broken” between them.15 In this brokenness of reality, the imagery of “the forearms” loses its charm to connect the narrator and Nagwa.

The imagery of “the forearms” appears for the second time when the sight of a woman in “sleeveless white dress” on the metro inspires the narrator’s imagination of his sexual intimacy with her where “her bare arms are next to [him]”16. The imagery of the bare forearms initiates the narrator’s imaginary physical interaction with the strange woman, in which body parts—breasts, nipples, hands, cheeks, lips—come into touch one after another until they end in each other’s arms. While in reality, the distant sight of the woman is transient and fruitless, the prolonged imaginary sexual encounter ends in the desperate narrator’s triumph over the woman’s reservedness.

By appealing to the physicality of the two women in the description of these imaginary sex scenes, the narrator shows that these sexual encounters connecting two individuals are fundamentally visual encounters aided by imagination. The imagery of the forearms objectifies the two women into abstract body parts—cylindrical geometric shapes, which become an available embodiment of the inaccessible whole for the viewer (in this case, the narrator). In his perception of the abstract forms, the narrator’s imagination opens up an intersubjective space where these abstract forms regain their physicality by coming into contact between two individuals one after another until the universal form of a human figure is recognized and the humanity of the visual objects restored. From the abstraction of their body, the narrator engenders an imaginary unity with the two women in view of reclaiming their individuality in the intersubjective space between them.

This unity between two individuals is intersubjective, which creates a stark contrast with the rhetoric of statist Pan-Arabism. Instead of evoking the collective through the individual, this rhetoric “rectifies the individual in the body of Pan-Arab state,” which is promoted, with the use of metonymy, as the embodiment of the unified nation, its popular sovereignty, and its willing subjects.17 With an emphasis on the symbol rather than the symbolized, the metonymy of statist Pan-Arabism deprives Arab people of their individuality in the name of unity and alienates them from one another in false representation. In That Smell, the narrator’s unproductive experience in reality reflects the aftermath of statism in the individual. In the narrator’s minimalist approach to the real world, the imagery of the forearms becomes the only representation of the two women’s sexuality. This violent representation diminishes their individuality, rendering them inaccessible to the others as coherent entities. Indeed, caught in the contrast between the intersubjective and the real, the readers of these sexual encounters can most strongly feel the inadequacy of statist Pan-Arabism in the impotency of the narrator, the sexual apathy of Nagwa, and the “coldness” of the woman “in sleeveless white dress” 18.

Organized into oval and spiral shapes, Samir Rafi’s oil painting Untitled (1959) does not easily yield to fast interpretations either. On the contrary, the perception of the abstract forms engenders an intersubjective space between the viewers and the painting in which more in-depth meanings are revealed with the help of imagination. At first sight, the viewers can identify two axes in the painting’s composition. At their intersection lie its major subjects. Slightly to the left of the intersection is a spiral shape colored with high contrast—it has a flesh-color interior with a distinct outline whose color changes from orange and blue to purple and black. The relative position of the spiral shape in the foreground and the horizontal axis in the background indicates the use of a two-point perspective, while the black shades to the bottom right of the spiral creates the illusion of shadows and depth in a three-dimensional space. Behind the large spiral is a group of oval and cylindrical shapes that centers at the intersection of the axes and spans vertically. Most of these overlapping shapes’ colors are from the earth tone—a color scheme that consists of colors mixed with brown, which gives them another connotation of nature and life. The color, shape, and relative position of the painting’s two central figures all suggest physicality, reminding the viewers of the texture of human skin and the form of limbs and organs. The interpretation of these features gives way to the intersubjective space. In the viewers’ imagination, these abstract limbs and organs are pieced together to evoke the imaginary universal form of a human figure standing in three-dimensional space, with its head overlapping the vertical axis and its feet cutting across the horizontal line at the bottom of the painting.

Nonetheless, as the viewers’ eyes move away from the center, the spiral forms at the bottom left would blur the human figure that becomes clear in their imagination. Similar to the central figures in form, these smaller shapes occupy another focus point, which decentralizes the painting. However, unlike the central figures, they do not have a clear spatial relationship to the rest of the painting. The blue line that encloses the cylindrical form—which constitutes a part of the human figure—cuts through the interior of the blue circular form at the bottom. This indicates that the circle is supposed to stand behind the cylinder and the imaginary human figure. Nevertheless, despite their relative positions, the circle transgresses the boundary and encroaches on the interior of the cylindrical form. This arrangement problematizes the spatial relationship between the circle and the cylindrical form, which isolates the latter from the rest of the imaginary human figure, rendering it no longer an independent individual entity. The blurry boundaries between the two forms highlight their flatness, which restabilizes the imagination of the three-dimensional human figure back to the abstraction of limbs and organs on two-dimensional burlap.

As the painting simultaneously “offers promise of real perspectival space and thwarts that desire,” it drastically contrasts the imaginary against the real in the viewers’ perception.19 The individuality of the imaginary human figure that emerges in the intersubjective space mocks its abstraction stabilized in flawed reality, in which the human figure in its coherent entirety becomes unrecognizable. Read within the painting’s sociopolitical context, this seems to insinuate a cultural environment in which the individuality of its subjects, represented by the integrity of the human body, is constantly subject to the “relentless abstracting logic” of the metonymy of statist Pan Arabism that alienates people from their individuality.20 By engaging the intersubjective space, the painting ironically unveils the truth behind this beguiling rhetoric, which by emphasizing the trope of the unified state, stabilizes its people’s imagination to avoid individual interpretations.

Indeed, as Choucair promotes intersubjectivity in her letter, she by no means “[believes] in a static Arab society” 21. Instead of establishing a collective symbol, she suggests a collective epistemology through the intersubjective interpretation of visual art, which has the potential to genuinely bring Arabs together. In That Smell, the intersubjective space brings the alienated individuals into communication on equal footing by restoring the integrity of the human body. In Untitled (1965), the imaginary human figure that looms in the intersubjective space inspires the viewers to invest in its individuality, which becomes rather indistinct in immediate reality. The contrast between the intersubjective and the real reflected in That Smell and Untitled (1965) illustrates the differences between this epistemology and statist Pan-Arabism. That Smell begins with the perception of abstraction, proposes a way of knowing the world that mobilizes imagination, and evokes the collective in the individual to create unity. Untitled (1965) ends in the metonymy of the state as the embodiment of the united nation, highlights the immediate object of perception that re-stabilizes imagination, and engenders alienation by rectifying the individual within the collective. From this comparison emerges a different model of unity among Arab people that, instead of creating collective symbols, proposes a shared way of knowing the world through the intersubjective space.

Notes

1 Sun’ Allāh Ibrāhīm, That Smell & Notes from Prison, trans. Robyn Creswell (New York: New Directions Publ., 2013), 13.

2 John T. Chalcraft, Popular Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 320.

3 Yoav Di-Capua, No Exit: Arab Existentialism, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Decolonization (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2018), 110-112.

4 Ibrāhīm, That Smell and Notes from Prison, 80.

5 Ibrāhīm, That Smell and Notes from Prison, 90.

6 Iftikhar Dadi, “Abstraction in the Arab World,” in Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s-1980s, ed. Suheyla Takesh and Lynn Gumpert (New York: Grey Art Gallery, New York University, 2020), 56.

7 Saloua Raouda Choucair, “How the Arab Understood Visual Art,” in ARTMargins 4, no. 1 (Feb. 2015), 126.

8 Kirsten Scheid,“Toward a Material Modernism: Introduction to S. R. Choucair's ‘How the Arab Understood Visual Art,” ARTMargins 4, no. 1 (Feb. 2015), 108.

9 Scheid, “Toward a Material Modernism,” 113.

10 Nader El-Bizri, “A Philosophical Perspective on Alhazen's Optics,” Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 15, no. 2 (2005), 194.

11 El-Bizri, “A Philosophical Perspective on Alhazen's Optics,” 201.

12 El-Bizri, “A Philosophical Perspective on Alhazen's Optics,” 193.

13 El-Bizri, “A Philosophical Perspective on Alhazen's Optics,” 199.

14 Ibrāhīm, That Smell & Notes from Prison, 29.

15 Ibrāhīm, That Smell & Notes from Prison, 30.

16 Ibrāhīm, That Smell & Notes from Prison, 46.

17 Di-Capua, No Exit, 109-110.

18 Ibrāhīm, That Smell & Notes from Prison, 48.

19 Dadi, “Abstraction in the Arab World,” 41.

20 Dadi, “Abstraction in the Arab World,” 55.

21 Scheid, “Toward a Material Modernism,” 110.