Benedetta and the Influence of Women on Futurist Art

Melody Jiang - April 29, 2024

The Italian Futurist movement of the early 20th century was an artistic, philosophical and political movement that was deeply entrenched in masculinity and masculine values. Because of this, female futurists’ contributions to the movement were often disregarded by later scholars. However, there were still a number of women who significantly impacted the movement, including Benedetta Cappa Marinetti. Benedetta’s emphasis on maternity combined with her insistence on women’s natural artistic impulses led her to a framework of thought that would become the most influential challenge to established Futurist ideas on women, which can best be seen in her own development of Futurist aesthetics in painting.

The Italian Futurist movement of the early 20th century was one based on speed, virility and dynamism. The movement, begun in 1909 with the publication of the Manifesto of Futurism by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, was one that encompassed all aspects of life– writing, poetry, philosophy, art, architecture, fashion, even homeware and toys– it was a movement that aimed to encompass all aspects of life. It was also the movement that notoriously birthed the rise of fascism and expressed a “contempt for women” (disprezzo della donna).

The disprezzo della donna has made many scholars characterize Futurism not only as a “masculine” movement, but also one that is actively anti-feminist. Thus, the presence of female Futurist writers, thinkers and artists can seem paradoxical, but this “contempt for women” is not merely a disdain for the female gender in general. To futurists, women represented everything that was “past-oriented rather than future-oriented”; they were “[slaves] to sentiments and sentimalism.” (Re 254). It was because of the societal role women had largely been delegated to– housewives who did not really participate in society and certainly not in the technological innovations found in the factories– that the futurists had expressed the disprezzo della donna.

Although texts on the idea of “women’s natural inferiority to man” were incredibly popular among intellectuals at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, and certainly influenced the Futurists, the Futurists were hardly advocating for the man’s total domination over women. In fact, Marinetti, the writer of the Futurist manifesto and the founder of the Futurism, had defended the (limited) women’s movement in Italy, although he was not “advocating so much the liberation of woman from the confinement of her traditional roles” but instead “the liberation of humanity at large from the slavery of human sexuality and sexual difference” in a social and cultural sense (Re 259).

The interest in eliminating “sexual difference” is related to the idea of simultaneity (simultaneità), “a theme dear to the futurist imagination” (Re 267). Valentine de Saint-Point, an early female futurist thinker, believed in a “superhuman” being that was not a true man or woman, with an “emotional and intellectual range including both male and female elements”, which references that idea of simultaneity (Re 261). Thus, the futurists did not truly believe in a gender hierarchy as the disprezzo della donna might suggest, and both male and female futurists were interested in the idea of eliminating gender difference entirely.

But despite all this, Futurism always remained a male-dominated movement, and scholarship on the Futurist movement that largely disregards women’s participation in the movement suggests that the female Futurists had limited influence within the movement. However, there were still many female futurists, the most influential of them all arguably being Benedetta Cappa Marinetti (known as just Benedetta), the novelist, poet and painter best known for being Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s wife. For some Futurist scholars, Benedetta acted simply as an extension of her husband, as she “increasingly stressed the theme of motherhood as the only true call for woman in the modern world,” an idea that went hand-in-hand with Fascist ideals (Re 277).

Benedetta’s emphasis on the importance of maternity was a unique stance amongst other female futurists. Many female futurists, including Valentine de Saint-Point, embraced the Futurist disprezzo della donna in order to challenge bourgeois associations with femininity, calling for greater “sexual freedom and the celebration of female animal instinct” (Larkin 448). On the other hand, Benedetta’s embrace of motherhood seems to be less revolutionary, recalling such conservative values that helped birth the rise of Fascism. Despite almost contradictory approaches to the “women question”, Benedetta wasn’t necessarily retaliating against the ideas of other female Futurists. Futurism was “a movement that embraced contradiction at its very core” and “women writers were drawn to a movement as varied and provocative as Futurism” with all of its “possibility, contradiction and transformation” (Larkin 449).

Benedetta was very insistent on the idea that women, as creators of life, “literally [embodied] the creative process” and so they had in themselves an artistic creative power that was on par with those of their male counterparts (Larkin 456). It was because of this equality of artistic power in men and women that Benedetta argued that men and women should both be “creative [co-equals] in the futurist revolution (Larkin 446). But Benedetta did not see these ‘procreative’ and ‘artistic’ forces as the same thing, and she clearly delineated a difference between the two, declaring that these “impulses may– indeed must– coexist” (Larkin 454).

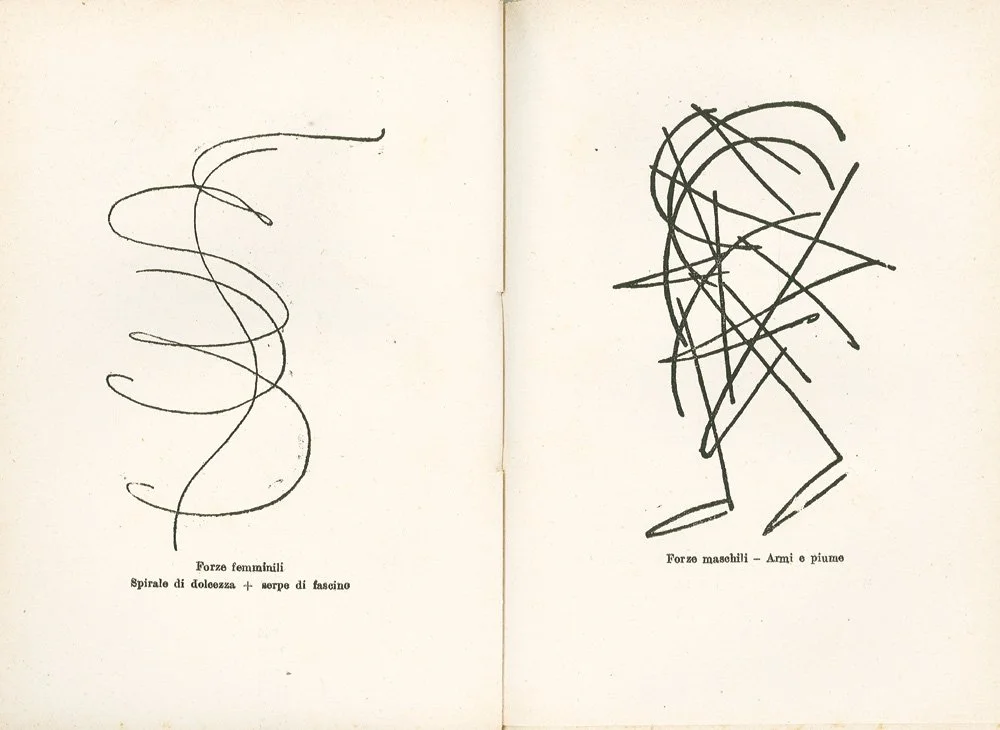

Figure 1: Benedetta Cappa, Le forze umana, 1924.

Benedetta’s insistence of these “impulses” simultaneously existing within women is also related to the Futurist idea of simultanietà discussed earlier, however, this simultaneity is not attributed to men. Because of this, it could be argued that this particular combination of forces that exist in women is what allows her to create a different, more revolutionary art. “Men,” Benedetta claimed, “often bring to art the sense of struggle; modern woman brings and must bring to it the love of life” (Larkin 455). This different approach to creation would manifest itself in an evolving difference in the aesthetics of the art produced, especially in Benedetta’s own works.

Benedetta illustrated examples of these differing artistic approaches in graphic sketches that appear in her first novel, Le forze umana (see figure 1). In a side-by-side comparison sketches, Benedetta compares her abstract interpretations of “Forze femminile” and “Forze masehili.” The sketch titled “Forze maschili” is subtitled “Armi e piume” which translates into “arms and feathers” (Larkin 456). The sketch abstractly represents a human-like figure, especially with what seems like legs and feet that emerge from a tangle of thick, forceful lines. Two lines that form a 45 degree angle create an open triangle shape that seem to make up the bulk of the body, a series of curved lines towards the top of the figure recall the plumes (“piume”) of a galea, and a long, diagonal downward stroke could be interpreted as a spear (“armi”) that the figure is grasping. The image that Benedetta creates is violent and warlike, and echoes her ideas of the “struggle” that Futurist men approached art with.

Figure 2: Benedetta Cappa, Synthesis of Aerial Communications (Sintesi delle comunicazione aerea), 1933-1934, tempera and encaustic on canvas.

Benedetta’s illustration of “Forze femminile”, however, is slightly harder to interpret. It is subtitled “Spirale di dolcezza + serpe di fascino” which translates into “spiral of sweetness + serpentine fascination” (Larkin 456). There is a somewhat vertical line that a series of thin, fluid lines spiral around– the vertical line could be interpreted as the “spine” of a human figure, but otherwise this sketch is not as obviously a human-like figure as the “Forze maschili” figure is. Interestingly, Benedetta has ascribed two characteristics to the “Forze femminile”, whereas she has only ascribed one characteristic to the “Forze maschili”, perhaps a nod to the simultaneità that exists within women. In this case, “sweetness” and a “serpentine nature” – two seemingly contradictory traits– are attributed to women, and could be interpreted as a woman’s seemingly simple, sweet nature masking a more shrewd and discerning nature within. The general underestimation of women, which Benedetta seems to be commenting on here, could be how she viewed women who lived in a world dominated by the Futurists and their masculine values.

The “Forze femminile” sketch is not as straightforward as the “Forze maschili” sketch and through simultaneità represents the greater complexity of the nature of women and the art she is able to create. In addition, the aesthetic approaches illustrated in the sketches reflect the two approaches to art, not only in the figures depicted but also in the difference of the type of lines that make up the two figures. Two futurist paintings, one from Benedetta, entitled Synthesis of Aerial Communications (Sintesi delle comunicazione aerea) (Figure 2) and one from the male Futurist painter Ivo Pannaggi, Speeding Train (Treno in corsa) (Figure 3) can act as examples of Benedetta’s “theory” on the feminine and masculine approaches to art.

Figure 3: Ivo Pannaggi, Speeding Train (Treno in corsa), 1922.

Although it can hardly be said that there are “rules” to Futurism painting, there are several key principles of the Futurist art movement which both paintings embody, making them both very typical examples of Futurist art despite other differences in aesthetic approach. Futurists aimed to express “cosmic dynamism” through the “inner vibrations, [and] the reciprocal emanations [that become] geometrical figures, lines, surfaces, and volumes, plastically diversified through form and color” (Trillo 83).

The forms, or subjects, of the paintings– Benedetta’s aerial landscape and Pannaggi’s train– are created through the use of “force lines”, which is a “‘direction of color-form’” that represents the “‘movements of matter along the trajectory determined by the structure of the object and its action’” (Trillo 91). In Treno in Corsa, different types of lines radiate from the train (itself created out of two diagonal lines that form a rapidly advancing triangle shape), creating geometric shapes that radiate the overwhelming speed and power being emitted from the train as it nears the viewer. Like the term “force-line” suggests, these “lines” aren’t necessarily drawn out, instead, they are more like a break or distortion in color, and they create the sense of a line separating two different planes.

But like Benedetta’s sketches, the form the “force-lines” take differ among the two paintings. Pannaggi’s powerful, directional lines express a “sensation of velocity” and urgency that Benedetta’s slowly undulating, exploratory lines do not (Trillo 87). While her lines do express the same kind of distortion as Pannaggi’s, there is no clear direction to her lines, allowing the viewer to analyze the painting from bottom to top or top to bottom. Additionally, it can be argued that she “riffs” on the types of lines in Pannaggi’s work and those of other Futurists– not only does she bend and twist this line, she widens it and gives it a form. In this painting, it takes the form of clouds that separate the different “land-forms” that the painting is composed of.

Benedetta and Pannaggi also employ very different color palettes in their respective paintings. Futurist artists did not exclusively associate with any signature array of colors, however, “they recommended the use of violent tonalities, the employment of pure colors” (Trillo 100). Comparatively, Pannaggi’s richly hued reds, greens, blues, yellows and blacks seem much more “violent” than Benedetta’s palate of muted cool tones.

In general, it seems that Pannaggi sticks much more closely to typical Futurist themes in his painting– the centrality of technology, and the depiction of such masculine values like speed, power and violence– this image lines up perfectly with the abstract warrior-figure in Benedetta’s “Forze maschili” sketch. Meanwhile, Benedetta takes these themes and transforms them into something that is unique to her, seen through her subversion of typical “force-lines” and “pure colors.” Even technology is pushed to the side, with only one wing of an airplane briefly cutting across the top half of the image, while the focus is retained on the various landscapes below.

Pannaggi’s painting is wholly dominated by a violent velocity while Benedetta’s allows for creative exploration and imaginative thinking in her fantasy-like world. These aesthetic differences, Benedetta argues, stem from that difference in approach to art mentioned above– “the sense of struggle” versus “the love of life” (Larkin 455). Only women, as both mother and artist, could possess the kind of love and creativity needed to actively contribute to the evolution of Futurist ideas, and through ideas, art. This is the idea of women that Benedetta wanted to express to the world, and her “radical reformulation of the founding futurist manifestos [sought to overturn] the destructive potential of early futurist rhetoric; she instead [privileged] a creative one” (Larkin 446).

By insisting upon and demonstrating the different perspective to Futurist art that women could bring, Benedetta argued that women deserved to be just as acknowledged to the development of Futurist aesthetics and ideas as men. Although many have disregarded Benedetta because of her “conservative” insistence on women as mothers, her take on the issue of the kinds of roles women could occupy allowed her to become one of the most influential female Futurists, and indeed one of the most influential individuals of the entire movement.

Bibliography

Cappa, Benedetta. Synthesis of Aerial Communications (Sintesi delle comunicazione aeree). 1933-34, Il Palazzo delle Poste di Palermo, Sicily.

Cappa, Benedetta. Le Forze Umane: Romanzo Astratto con Sintesi Grafiche (Human Forces: Abstract Novel with Graphic Synthesis). Franco Campitelli Editore, 1924.

Larkin, Erin. “Benedetta and the creation of ‘Second Futurism.” Journal of Modern Italian Studies, vol. 18, no. 4, 2 Sept. 2013, pp. 445-465. Taylor and Francis Online, https://doi.org/10.1080/1354571X.2013.810802

Pannaggi, Ivo. Speeding Train (Treno in corsa). 1922, Museo Palazzo Ricci, Macerata.

Re, Lucia. “Futurism and Feminism.” Annali d’Italianistica, vol. 7, 1989, pp. 253-272. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24003870

Trillo Clough, Rosa. Futurism: the story of a modern art movement, a new appraisal. New York: Philosophical Library, 1961.