An Interview with Victor Ehikhamenor

Aimee Resnick (she/her) - November 19, 2022

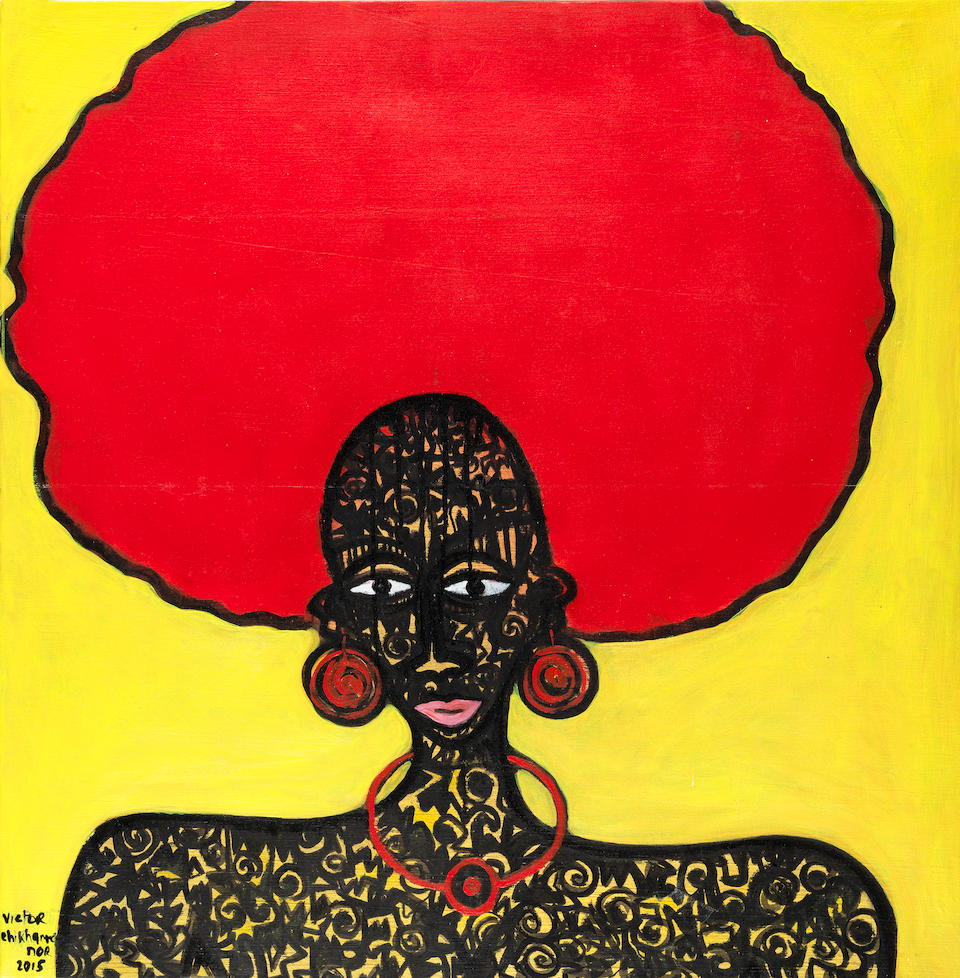

Victor Ehikhamenor is a multidisciplinary Nigerian artist best known for work engaging African culture and politics. Heavily guided by tradition, the artist melds Catholic emblems, obsessive calligraphy, tangible voids, and visual jumble to create innovative portraiture of Africa. In 2017, Ehikhamenor served as the first representative from Nigeria to the Venice Biennale. Recently, he was described as "undeniably one of Africa's most innovative contemporary artists." We sat down to discuss his art, Nigerian life, and the lasting legacies of colonialism.

NAR: Thank you so much for taking the time to chat today. Your work is unique in its complexity and syncretism between Nigerian art and Christianity: do you mind giving our readers a note on the traditions that inspire your art?

Ehikhamenor: It's interesting that [Nigerian art and Christianity] are converging now for the world, right? That people are beginning to make the connection between my work and those works. But you have to realize that I'm part of that culture. I'm part of that tradition. That is where I got my early inspirations from growing up. I grew up among these things. You understand? This is the work of my people and this is what we have always done. That the world is just realizing now doesn't mean that we just started or that I just started referencing the work of my people.

Art making is a way of life for us. It's not something that we create to sell or because we have a museum show or to show it to people. It's a way of life, where I'm coming from. It's like when you go to a fishing region of any part of the world, that a lot of people fish there. Or you go to the Midwest, and you see that every family has somebody that has worked in car manufacturing. So cars, or repairing cars or fixing cars or enhancing cars would not be something that is strange to somebody that comes from a background like that. So for me, you know, art making in that sense of the diffusion of two religions is something that we have done for centuries in our region.

NAR: What does this traditional way of life look like in terms of art making and practice?

Ehikhamenor: I mean, apart from the fact that you have individual artists that have their own individual practice in the entire entire Benin kingdom, there is primarily an organized guild of bronze casters that have been there for the longest time. For centuries they have been making works either for themselves or the king. That has never stopped. It passes on from this guilt, from family to family, like an inheritance. There are about several guilds or several families that produce some of the finest bronze that you see in museums. Items like cups, water jugs, headrests, thrones, portraits, archival materials, and illustration.

We told our stories through bronze casting. When you look at those plaques, those you see maybe in the British Museum or the Metropolitan, these are our stories. These are our ways of documenting and recording past and present events. A visitor could come to the King’s palace and he would call one of the best bronze casters to come and take a visual picture to provide memory of that event and give that narrative to future generations upon generations. So we told our stories without a western writing system. We wrote with visuals, narratives through bronze and other means of art. That is part of our culture.

In the process of this art making, there are events that lead up to it. Activities around art making like dancing: on days that they are casting bronze, the community will come together and have prayer and dance sessions before they start casting. Again, a lot of the things revolve around making in that region of the world, you know? Creation is key to our culture.

NAR: The Rosary Series is particularly impactful for me in its discussion of globalization, environmental degradation, and religion. What inspired this series and how has it evolved over time?

Ehikhamenor: Religious iconoclasm is not peculiar to [Nigerians]. As much as the west may want to bend it towards that. Religion is one of the biggest producers of art across the world. You go to the Vatican, you go to Italy, and you find that our way of keeping religion is through art, right? That is not different from [Nigerians] at all. Fast forward to the 16th century, we had our first European visitors when the Portuguese visited the kingdom and introduced Christianity. So since the 16th century, our people have incorporated Christianity into traditional ways of life. This can be seen in our crosses, in the sense that we don’t use the crucifix. Our own crosses come from a four-way juncture of roads, which is central to our cosmology. That is, when we want to make a sacrifice, it has to be at the fourth junction. It's where the spirit world meets the real world. So that's where that whole cross comes into our own iconographies.

We have a way of commemorating our ancestors. We use art to commemorate our ancestors. We have them in our shrines. We have them in our places of worship, just like you will find a crucifix in a church or the portrait of Mary in a cathedral.I can’t recall any church in the Western world that doesn't have any statues or painting, or stained glass. So in our own way, we commemorate our ancestors and our saints. Colonialism tends to make their fetish, to try to give us a bad name. But you have to realize that there was a religious and culture war that was mounted against my people. If you destroy people's culture, you can completely make them believe in your own culture. That is what happened to a lot of African heritage. Because colonialism came and told them that their ways of life were worse than anything that has ever happened to humanity. And then, before you realize it, all the works that were made were brought to Western museums, you know?

NAR: Recently, you published an opinion piece in the New York Times calling for the bronzes to be fully returned to Nigeria. Many of our readers are unfamiliar with the bronzes: can you walk us through their history and the repatriation effort?

Ehikhamenor: We're not necessarily saying they should be brought back to the museums. Of course we have the Benin Museum for them, but we are saying that they should be brought back so that they can continue to be functional. African countries didn't make this art for art’s sake. They were functional arts. They are things we use in commemorating our ancestors, things we use in communication with the spiritual world. So these things were taken from us, and I think they should be brought back at the appropriate time.

Now there are more people realizing we still need them in our community. The community from which they were stolen still exists. They are looted objects. They are stolen objects. They were taken from Africa forcefully, and a lot of people were killed. Women and children. If you find any Nazi looted object in the world, they are returned to the owners. We are trying to apply that same standard to works that were stolen from Africa, stolen from Benin, stolen from Ghana, from Kenya, from Ethiopia. I think it's wrong for humanity. I think colonialism is inhumane. And I think it's about time we start righting those wrongs.

NAR: You also recently completed an installation work on the ransack of Benin- can you expand on your recent work Still Standing?

Ehikhamenor: In 2021, St. Paul hosted a project called “50 voices, 50 Monuments.” My work at St. Paul was an invitation to respond to a plaque. The plaque was commemorating the admiral that led the attack on the Benin Kingdom. They called different artists, poets, and writers to react to each monument. I was invited by the curator to respond to that plaque of the Oba that was on the throne at the time [of the ransack]. I decided to make a portrait of him the way he would've dressed because there is no picture of him dressed as a king. All of the pictures of our king that we have in archival files depict him dressed as an ordinary citizen of Benin. I think the world needed to see the way the king would have dressed in 1897. Number one, it's a way of correcting oppression. Number two, it is to reawaken that history which people are often not familiar with. To be invited to a place like St. Paul was quite important, as it opened up conversations where past black artists would never have dreamt of having their work displayed. It was a super exciting installation.

NAR: You founded Ink Not Blood to discourage violence after delays in election processes - can you explain the initiative's goals, programming, and successes?

Ehikhamenor: I moved back to Nigeria in 2008 after close to two decades in the United States, where I was exposed to different politics. I grew up in Nigeria on military regimes. While I was in the US, we returned to democracy. I realized that elections are still very violent in Nigeria, I needed to do something as an artist. I started that to encourage people, both young and old, to vote with ink and not blood. We had a really strong campaign during the elections I witnessed. To make sure that we can vote and have the best democratic situation possible without having to have so much acrimony and fighting and division. You know? So that’s the movement that I started and I’m hoping that young people in other countries will buy into it. I use it to encourage a peaceful democratic transition when we change government in Africa, Nigeria particularly.

NAR: What do you wish Americans understood about Nigerian politics?

Ehikhamenor: There is not that much difference between the United States and Nigeria. Nigerian Democracy is young when you compare it to American democracy. Right? I mean, what we are going through now is what Americans went through with the Civil War. It takes time to have a robust democracy. I think Americans should not claim we are a completely failed system, as this is forgetting their own history, forgetting that they fought themselves before they were able to find a common ground, too.

Humanity is very autocratic. Humanity is very dictatorial. By claiming people of diverse groups and cultures should come together and work in the democratic situation: it takes time to build trust. So the American audience should remember that not having a smooth election transition is not peculiar and that stable democracy takes time.

NAR: Where do you think American perceptions of African government come from?

Ehikhamenor: There's a lot of global propaganda about superpowers and politics. I would say that it's a colonial hangover. A lot of people are not familiar with the region and its workings, but a lot of people also are quite familiar with it and would rather continue with the old narrative. We need to write our own histories to be able to correct these narratives. Americans have their own way of looking at things. People look at Africa from far away, they have never visited Nigeria or African countries and have only been exposed by Hollywood or history books. It's secondhand information. When you consume secondhand information, there's a risk that things are not quite right.

NAR: What can our student readers do to support repatriation efforts?

Ehikhamenor: They can constantly write about it. Constantly call out the institutions still holding tight to these looted objects. By creating awareness that these things were taken under a very scary condition. The people need to know that these things were stolen from people with a deep need for them. So don't tell us that the world needs to see these things in museums. I think it is misleading to say one can understand other people's cultures through museums. The younger Americans must kick against that to say that it is wrong for other people's culture to be ransacked and looted. Restoring ownership of these things resides with those that are rooted in the wrongness of ransack. I think that would be a place to start.

Please note: this interview has been edited for length and clarity.