An Interview with David Ocelotl Garcia

Aimee Resnick (she/her) - January 31, 2024

David Ocelotl Garcia is a Denver-based visual artist who works in Abstract Imaginism – a style of art that combines the spontaneity and unpredictability of abstraction with the creativity and perception of his imagination. David has created over two dozen public art pieces that can be found nationwide, including murals, sculptures, and installations. One of these installations, the Earth Spirits installation, is prominently featured at Meow Wolf Denver. He also specializes in bronze and illustration work. This week, David told me the stories of his most recent projects: the Huitzilopochtli Mural Restoration and the National Western Center Bridges Art Project.

NAR: Tell us about the energy of art. Does all art have energy?

Ocelotl Garcia: I'm still learning, to be honest. I think art’s just been around for so long - it’s a manifestation of energy at its core. Art is a living being that's alive.

It has to do with quantum physics. I've always been fascinated by physics. It makes a lot of sense to me how things don't make sense. Everything has a life force, be it paint or a plant.

Every piece of art has a certain amount of energy because of its act of creation: art has the ability to absorb our energy. Like a battery, that's what art is. It gets charged by the artist's energy.

But art can also give off energy. A mural can emit energy based on the interaction of the community with the artwork. I like to understand art like a tree that needs to be nurtured and that provides shade.

Art gives back to me in the form of understanding my reality. But it has an even more meaningful purpose where there’s community. It gives to people.

NAR: In 2020, your historic mural on West 8th Avenue in Denver, Colorado was painted over. This summer, you had the opportunity to restore the mural to its original, fantastic state. Tell us more about recent efforts to preserve historic Chicano murals in Denver.

Ocelotl Garcia: It's on 8th and Federal in the Sun Valley neighborhood. I created that mural in 2007: it was my first-ever public art piece. It was spontaneous and organic. I’ve always followed my instinct and intuition as an artist.

The way this mural came about was very personal. The building was actually a foundry where I did a lot of my sculpture a long time ago. I had gone to meet the tenants that were going to occupy the new building across the way. While we were chatting, they told me that they were going to open a community center in the area with an emphasis on native history and tradition. Then they asked if I would be interested in creating a mural for the center.

That really resonated with me. I had never created something public before. I had never shared my interpretation of Native culture or my voice like that.

To open the center, the community had to do a lot of healing. We needed to combine the mind, body, and spirit of the community. So the purpose of this mural was to help aid that process. We did that through the participation of the community in the mural’s creation. We held several therapeutic workshops and the mural evolved out of what was shared.

The mural became the visual language, the voice of the center. But eventually the community center moved out of the building to a new location. And then a dispensary moved into the space about three years ago.

There was some miscommunication. People are always driving through the neighborhood, and people there are familiar with the mural. Somehow, the community knew how to contact me. One day, I got a call that the new tenants had painted over my mural. So I went to visit, and their intention was to paint a new mural related to their business – but they failed to realize that their contract prohibited them from painting over any of the artwork on the building. It was drama, just back and forth drama.

By this time, I was already working with Lucha Martinez on the Chicano Murals Project. Lucha is fighting for Chicano murals across Denver, so she jumped on this right away, and started to call other organizations and rally the community.

So I wasn't alone. I had everyone supporting me, which was really amazing.

We challenged the company who had painted over my mural. We sent them a letter saying that we were prepared to take legal action in its fullest form. They challenged us back. They asked us, “why is this mural such a big deal?”

After a year of back-and-forth, the company had a sudden change of heart. They asked how they could fix the situation, and so we asked them to pay for the repainting of the mural. I put together a quote, and they were pretty taken aback from the cost. Still, they were willing to pay for the damage, and we recovered from any resentment and anger.

During this process, Lucha was connected with an organization in California called Spark. Spark was restoring murals. Spark really inspired Lucha: before, we assumed we would have to repaint the entire mural. After talking to spark, Lucha was confident that we could remove the paint and restore it. That blew my mind.

It changed everything. How powerful is it to restore erased art instead of recreate it? So I traveled to LA myself and met with Spark and learned the restoration technique. It took me a year to learn. During that time, the mural just sat under the primer.

I started with a test sample. When I first saw my mural emerge from the white paint, it became actually a reality that I could restore my work. I could see it was working.

So another year passed and then we started cleaning the mural. It worked. It was amazing. It was like magic, right? So people got real excited, and Lucha got real excited thinking of all these other murals that were sitting under primer around the city.

This summer, we touched up the mural and got it back to its original self. A few months ago, we got it all sealed up with a protective coating. The last step was an unveiling. We called it The Reawakening, which was just a few weeks ago. It was sleeping under that primer, and now it's back. We held a tribal blessing, and it was an amazing day.

Another beautiful thing: with the restoration funding, we were able to complete another mural on the west side of the same building. We were able to create more. From one, we got two.

NAR: What does the mural mean to the Sun Valley community?

Ocelotl Garcia: For the people who visited the community center, the mural was a representation of their own healing. In a gentrified world, it is a way to process memories, you know. A lot of the kids who helped create the mural are now adults. The mural recorded their youth – I recorded their past.

It's also a representation of Sun Valley’s cultural identity. As neighborhoods get gentrified, everything gets erased and it's like a whole new place. The mural depicts the culture of Latinos, Mexicans, Chicanos. It has a lot to do with identity.

This mural is very important because our native identity isn’t something they teach in school. People always tell me how they see themselves in the mural. They say it’s not just an image, but their family and their ancestors.

I thought that was really beautiful. That's always stuck with me. The mural’s become a living thing. Like a tree that’s been there for many years, it just keeps growing.

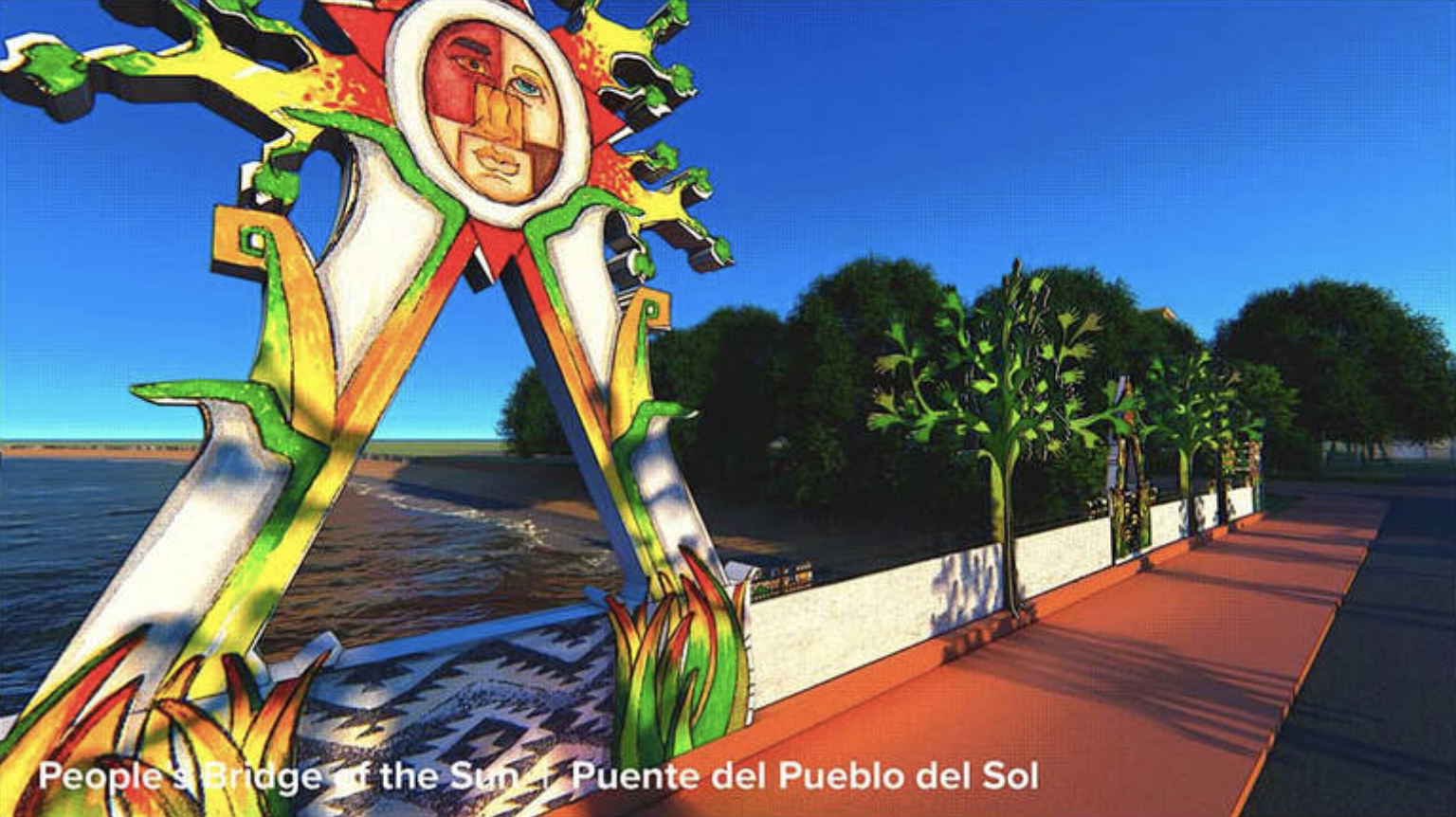

NAR: I want to talk next about your People's Bridge of the Sun and People's Bridge of the Moon. You created these pieces for the National Western Center Bridges Art Project, which connects The National Western Center with its neighboring community. For this project, you hosted several public art workshops with youth. Tell us the story of this piece.

Ocelotl Garcia: It didn't start with a name, it was just the Bridge Art Project. That was about five years ago – five years seems like a lifetime to me at this point. It was a partnership between Denver Arts and Venues, the City of Denver, and the National Western Stock Show. The Stock Show was building a new campus with an amphitheater and state-of-the-art learning facilities. All these amazing things.

So they wanted to build two bridges to connect the campus with the neighborhood. They were to serve as access points. The term “bridging” was very powerful for the project. It was about bridging the community.

At first, I wasn't going to do the project myself. I didn't think I was prepared to do the project. It was such a big endeavor. I felt like I wasn’t quite ready to build something that large. And so that was my mindset. I wasn’t even going to apply.

But things are organic. I felt my instinct. I felt like this project was trying to speak to me. I have a friend in Chicago, and he was approached by a group that wanted to apply for the project. They asked if he knew any artists in Denver, so he called me and asked if I would join their team.

I just remember thinking, why not? The team in Chicago will do all the paperwork: I just have to apply using my portfolio. We turn in the application and, a few days later, they let me know that we’re finalists for the proposal. My jaw dropped. I just couldn't believe it.

When you're a finalist for a big bid, you have to propose a project. I got to visit the site and was truly inspired. So I started designing, and I found the concept for the People's Bridge of the Sun and the People's Bridge of the Moon. I was thinking about how nature meets humanity. It just sparked my passion and we worked and worked and worked.

One of the really challenging things for me was the community engagement portion. Community engagement was outlined in the contract, but it wasn’t a get-it-done kind of thing. Our team was all deeply passionate about connecting with the community. We wanted to involve as many people as we could find from the community in a meaningful way, especially families.

My friend from Chicago is amazing at creating healing spaces through art. Together, we landed on having people create self-expressive clay sculptures that would become part of the bridge. And so we hosted and recorded a mock community engagement session as a part of our proposal.

One of the coolest experiences I’ve ever had was proposing our concept to the executives. It just clicked and we knocked it out of the park. That was such a cool feeling. At the end of our pitch, they unofficially offered us the project. I was so excited!

Let’s see. It took us over five years to build the Sun Bridge; we haven't built the Moon Bridge yet.

We started by spending a year designing our community workshops. As far as I know, the People's Bridge of the Sun has involved the biggest community engagement endeavor in the history of the United States. We did workshops all over Denver. We went to schools, senior centers, and recreation centers and helped people create over one thousand self-portraits out of clay. All of these portraits are visible now on the Sun Bridge. You can see all the different faces of the people who interacted with the project.

Before, we were talking about energy. It doesn't matter if you're an “artist” or not, when you're creating something, you're transferring your energy into the material. All these people transferred that energy into the People's Bridge of the Sun. One thousand people’s energy is sitting there on the bridge.

We met with so many children and families. Now, they all live in these sculptural faces and pieces. They're all so different and interesting and vibrant. You could sit there forever feeling the energy of all these different pieces and people.

Please note: this interview has been edited for length and clarity.